A little late with this baby. Next year, I resolve to get my last few books written-up and posted before the holidays are over!

Overall, I'm quite happy with my performance this year. I really wanted to ensure that I would reach 50, as I had slipped the two previous years. I pushed hard early in the year and was well on track, actually cruising to easily break my record. But I got derailed. Mostly by gaming (Draconis is in the beginning of October and caused a big flurry of one-shots afterwards), though perhaps other bad habits got in the way as well (hello, internet!). But I pulled through in the end and have achieved my goal. Not that the quantity of books is so important, but having that goal really helps to remind me when I'm not reading and need to get started again.

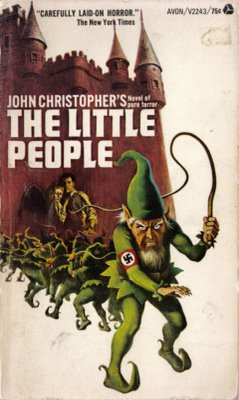

It was an excellent year for Post-Apocalyptic literature. I (or others, especially Lantzvillager) found and read a lot of lesser-known works to the extent that I feel that I have a decent grasp of the genre now. In particular, I devoured a lot of John Christopher. For some reason, his weird mix of British sexual anxiety and social criticism really appealed to me. I have a couple more of his books on deck and I will continue to seek him out, but my burning fire has reduced itself somewhat to more of a glowing coal. He will be someone I'll continue to read from time to time, but I won't actively seek out.

I also gained a greater appreciation of the hard-boiled genre, particular through August West's excellent blog. I had the perception that most of those pulp crime books were of a less quality than the really well-known names, enjoyable but more for the genre elements than any innate excellence. I am glad to have been disabused of that notion, discovering that there is a world of top-notch writing and storytelling buried in those (sadly) crumbling and hard to find old paperbacks. The only real problem is that they really are hard to find and becoming more and more recognized as having collection value, thus also more expensive.

My other highlight was my trip to Winnipeg which really revived my used books hunting instinct. I've been to the used bookstores in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal so many times now that it was all becoming a bit boring and dissatisfying. My trip to Winnipeg and the awesome used bookstore scene there created a feeling not unlike the jaded hunter the first time he decides to make man his prey. How it raises the blood! I don't know if I'll have the opportunity to visit any other middle-level city this next year. Halifax suggests itself as having potential...

Donald Westlake's death at the end of the year was quite shitty. It coincides with the re-publication of his stellar Parker series, 3 at a time, in order by the University of Chicago Press. I may buy those and re-read them (it will be the third time) in order to honour his life and work and help spread the word about their awesomeness.

Other than that, I don't have any particular goals for this year. I may not even push strongly to achieve the 50. I would just like to read a little more consistently and perhaps absorb a bit more. For the 50 books community, I hope for continued activity and participation among all the blogs. I think we are all more motivated when we received comments and I thought we had a strong year this year. Great work everyone!

Onward to 2009!

Over the holidays, we went out to the teeny

Over the holidays, we went out to the teeny  I was at home over the holidays and really in the mood for a good, British mystery. My dad recommended this one from my parents' excellent collection of paperback mysteries and it definitely satisfied my needs! I had seen this book lying around for years and I always thought, mainly because of the early '70s and genericy mystery cover that it was perhaps a decent read, a nice little find by my parents that they thought good enough to not let go of. Turns out it is actually a classic of the genre, well-received upon publication and considered today among aficionados to be one of the best of these kinds of mysteries.

I was at home over the holidays and really in the mood for a good, British mystery. My dad recommended this one from my parents' excellent collection of paperback mysteries and it definitely satisfied my needs! I had seen this book lying around for years and I always thought, mainly because of the early '70s and genericy mystery cover that it was perhaps a decent read, a nice little find by my parents that they thought good enough to not let go of. Turns out it is actually a classic of the genre, well-received upon publication and considered today among aficionados to be one of the best of these kinds of mysteries.  Doc gave me a beautiful old paperback copy of this under-heralded sci-fi classic. It's one of his favourites from his youth and he wanted to pass it along. You could technically put it in the post-apocalyptic genre, but it's truly a fantasy book. It's so far beyond the collapse of our modern empire that other civilizations have already come and gone. The advanced technological remains still exist in the ruins of the past and the unearthing and using of this old tech by a handful of what become, in effect, magic users, is the only PA trope that separates Pastel City from true fantasy.

Doc gave me a beautiful old paperback copy of this under-heralded sci-fi classic. It's one of his favourites from his youth and he wanted to pass it along. You could technically put it in the post-apocalyptic genre, but it's truly a fantasy book. It's so far beyond the collapse of our modern empire that other civilizations have already come and gone. The advanced technological remains still exist in the ruins of the past and the unearthing and using of this old tech by a handful of what become, in effect, magic users, is the only PA trope that separates Pastel City from true fantasy.

I found this one as well in Winnipeg. When I was a kid, we used to read a lot of British children's books, like The Box of Delights, Swallows and Amazons and even a ton of Enid Blighton (which I guess was looked down upon by certain people). These books always seemed to have a dark side to them and this became more explicit when I started reading the books aimed at adolescents from England. I remember in particular one that was called The Cage or The Cave or something like that which starts out with a guy waking up in a dungeon having no memory of who he is. He slowly meets some other people who are there also missing their memory. The book is about them exploring the place, finding out what is going on and who they are. It turns out they were all juvenile criminals and the place was an experiment in psychological manipulation and rehabilitation. I remember it being quite dark.

I found this one as well in Winnipeg. When I was a kid, we used to read a lot of British children's books, like The Box of Delights, Swallows and Amazons and even a ton of Enid Blighton (which I guess was looked down upon by certain people). These books always seemed to have a dark side to them and this became more explicit when I started reading the books aimed at adolescents from England. I remember in particular one that was called The Cage or The Cave or something like that which starts out with a guy waking up in a dungeon having no memory of who he is. He slowly meets some other people who are there also missing their memory. The book is about them exploring the place, finding out what is going on and who they are. It turns out they were all juvenile criminals and the place was an experiment in psychological manipulation and rehabilitation. I remember it being quite dark.

Whoah! I've got whiplash from slamming the brakes so hard on my book reading! I was whaling away with all the summer travel and being away from the distractions at home (i.e. the internet) but I hit a wall this winter. To be fair with myself, there has been a lot of productivity in other recreational realms (gaming, cooking, building and fixing stuff), but I really should have put away the 50 by now.

Whoah! I've got whiplash from slamming the brakes so hard on my book reading! I was whaling away with all the summer travel and being away from the distractions at home (i.e. the internet) but I hit a wall this winter. To be fair with myself, there has been a lot of productivity in other recreational realms (gaming, cooking, building and fixing stuff), but I really should have put away the 50 by now. I found this book in Winnipeg, looking for The Don is Dead by Nick Quarry on behalf of Lantzvillager. He will have to explain how he found out about this author, but I'm glad he did. This is good, solid, workaday crime writing that was enjoyable from start to finish. à

I found this book in Winnipeg, looking for The Don is Dead by Nick Quarry on behalf of Lantzvillager. He will have to explain how he found out about this author, but I'm glad he did. This is good, solid, workaday crime writing that was enjoyable from start to finish. à These well-known Napoleonic-era naval adventure books have been tempting me for years. I kept going back and forth with the slight hesitation that they were dumbed down and written for a mass audience. You have to be so suspicious of books that are really popular as they usually suck. On my trip to

These well-known Napoleonic-era naval adventure books have been tempting me for years. I kept going back and forth with the slight hesitation that they were dumbed down and written for a mass audience. You have to be so suspicious of books that are really popular as they usually suck. On my trip to  I found out about Wilson Tucker because I read somewhere that his book "Wild Talent" is considered the classic of the mutant human with super brain power being hunted by the authorities sub-sub-genre of books. I have yet to be able to find it, but I did find a couple of other books by him, including this one. It's about a guy who wakes up in some weird world run entirely by women. His memory of his past life is fuzzy, but he knows he came from the Midwest during WWII and that he was some kind of handyman.

I found out about Wilson Tucker because I read somewhere that his book "Wild Talent" is considered the classic of the mutant human with super brain power being hunted by the authorities sub-sub-genre of books. I have yet to be able to find it, but I did find a couple of other books by him, including this one. It's about a guy who wakes up in some weird world run entirely by women. His memory of his past life is fuzzy, but he knows he came from the Midwest during WWII and that he was some kind of handyman. I've heard a lot of good stuff about Elmore Leonard's westerns. He wrote them at the beginning of his career and they did fairly well but he moved onto crime at some point and never looked back. I was told that his westerns are quite easy to find, but it took me a trip to Winnipeg!

I've heard a lot of good stuff about Elmore Leonard's westerns. He wrote them at the beginning of his career and they did fairly well but he moved onto crime at some point and never looked back. I was told that his westerns are quite easy to find, but it took me a trip to Winnipeg! I found this little gem at Nerman's in Winnipeg. It was in the Action section (the existence of which gives me hope for the world) among a bunch of other Philip Atlee books featuring Joe Gall. I was only aware of them because Lantzvillager had asked me to find a specific one (The Green Wound Contract, which I later did find, but in the Vintage section and under the title The Green Wound). All the covers looked interesting, but I picked this one because of the Canadian content. Hell, the inner blurb reads "

I found this little gem at Nerman's in Winnipeg. It was in the Action section (the existence of which gives me hope for the world) among a bunch of other Philip Atlee books featuring Joe Gall. I was only aware of them because Lantzvillager had asked me to find a specific one (The Green Wound Contract, which I later did find, but in the Vintage section and under the title The Green Wound). All the covers looked interesting, but I picked this one because of the Canadian content. Hell, the inner blurb reads "

I was gripped by some insane frenzy while in California and purchased several new "trade paperbacks", including this first book of a series of cat fantasy books for young readers. I'm a big fan of cats and fantasy and had been curious about these when I'd seen them on the shelf, but they are so clearly commercialized from the start and there are so many of them, that I had never planned on actually reading them. But somehow I decided to take the plunge. I got #1, but it wasn't until I was about a quarter of the way through and totally mixed up about the characters, that I figured out this was the first book of the second series! This is why you shouldn't buy books like this on the spur of the moment! Let that be a warning to you, my friends.

I was gripped by some insane frenzy while in California and purchased several new "trade paperbacks", including this first book of a series of cat fantasy books for young readers. I'm a big fan of cats and fantasy and had been curious about these when I'd seen them on the shelf, but they are so clearly commercialized from the start and there are so many of them, that I had never planned on actually reading them. But somehow I decided to take the plunge. I got #1, but it wasn't until I was about a quarter of the way through and totally mixed up about the characters, that I figured out this was the first book of the second series! This is why you shouldn't buy books like this on the spur of the moment! Let that be a warning to you, my friends. Everybody loves to hear about rats and it's surprising that a book of this nature wasn't attempted before. Basically, the author decided to sit in a New York City alley for a year and observe the rats. I am always intrigued by the idea of these kinds of books (Salt, Cod, etc.), the idea that you can read a single, relatively light volume and have a nice general overview of the subject. But I can rarely actually bring myself to read them. The subject matter here convinced me to actually take the plunge. Rats got a lot of fanfare when it came out and I've been looking for it for a while. In a fit of consumerist frenzy, I bought it and several other trade paperbacks new at Dark Carnival! I don't know what's come over me. Perhaps it's the giddiness as I seem to be potentially capable of achieving my goal this year.

Everybody loves to hear about rats and it's surprising that a book of this nature wasn't attempted before. Basically, the author decided to sit in a New York City alley for a year and observe the rats. I am always intrigued by the idea of these kinds of books (Salt, Cod, etc.), the idea that you can read a single, relatively light volume and have a nice general overview of the subject. But I can rarely actually bring myself to read them. The subject matter here convinced me to actually take the plunge. Rats got a lot of fanfare when it came out and I've been looking for it for a while. In a fit of consumerist frenzy, I bought it and several other trade paperbacks new at Dark Carnival! I don't know what's come over me. Perhaps it's the giddiness as I seem to be potentially capable of achieving my goal this year.

I picked this book up from the same street vendor in Toronto who sold me Scapa Ferry and I really hemmed and hawed over it. On the one hand, the cover looked cool, just from the period I like (the height of Desmond Bagley's popularity). On the other, it takes place in the cold war and seemed to have a lot of military and espionage themes, which I am not so interested in (I don't mind the period, but I like the focus to be on adventure). Also, I was worried the whole thing would take place aboard some military ship. After reading it, I'm glad to say I made the right choice. Yes, the story is definitely in the context of the cold war, but the ship is sunk right at the beginning (it is the catalyst that starts the story) and the bulk of the narrative is about a plucky young reporter (whose father died on the ship) trying to find out what happened.

I picked this book up from the same street vendor in Toronto who sold me Scapa Ferry and I really hemmed and hawed over it. On the one hand, the cover looked cool, just from the period I like (the height of Desmond Bagley's popularity). On the other, it takes place in the cold war and seemed to have a lot of military and espionage themes, which I am not so interested in (I don't mind the period, but I like the focus to be on adventure). Also, I was worried the whole thing would take place aboard some military ship. After reading it, I'm glad to say I made the right choice. Yes, the story is definitely in the context of the cold war, but the ship is sunk right at the beginning (it is the catalyst that starts the story) and the bulk of the narrative is about a plucky young reporter (whose father died on the ship) trying to find out what happened. All this classic science fiction reading going on over at

All this classic science fiction reading going on over at  Except for Stepen King, I was never a huge fan of horror. But in recent years, with the influence of Meezly, Fantasia and other friends, I'm getting more and more exposed to it. One of those friends, Jocelyn, whom I met through gaming, is quite into it. He ran a very fun Unknown Armies, (which would some would say is the RPG that epitomizes contemporary horror) campaign that I played in and he lent me Dark Harvest. I have no idea how Norman Partridge came onto his radar, because I've never heard of him before, but if this book is indicative of his skill and style, he's good.

Except for Stepen King, I was never a huge fan of horror. But in recent years, with the influence of Meezly, Fantasia and other friends, I'm getting more and more exposed to it. One of those friends, Jocelyn, whom I met through gaming, is quite into it. He ran a very fun Unknown Armies, (which would some would say is the RPG that epitomizes contemporary horror) campaign that I played in and he lent me Dark Harvest. I have no idea how Norman Partridge came onto his radar, because I've never heard of him before, but if this book is indicative of his skill and style, he's good. I have to admit that I didn't read all of this book in 2008, and in doing so, reveal a little strategy I use to give me a slight boost towards reaching the goal of 50 books a year. I don't like buying books of short stories, even if I am a fan of the author, because I can rarely get through them. Every now and then, in the case of great authors (such as Doyle and Howard), I can not resist. My trick is that in between every book that I finish, if I don't immediately go on to another novel, I'll read a short story or two. Eventually, I'll complete the entire collection and get to add it to my list. Such was the case with

I have to admit that I didn't read all of this book in 2008, and in doing so, reveal a little strategy I use to give me a slight boost towards reaching the goal of 50 books a year. I don't like buying books of short stories, even if I am a fan of the author, because I can rarely get through them. Every now and then, in the case of great authors (such as Doyle and Howard), I can not resist. My trick is that in between every book that I finish, if I don't immediately go on to another novel, I'll read a short story or two. Eventually, I'll complete the entire collection and get to add it to my list. Such was the case with  CanLit time people! My boss passed me down this book while we were working together in Vancouver. Normally, I have a hard time reading these kinds of books, but it had a glossy cover and nice large margins, so I figured I could handle it. It's the story of a young black man in Ontario dealing with his mother's dementia. You can see why I might have normally hesitated! Sometimes, though, when someone random lends me a book, I'm quite motivated to read it. Can't explain it, but there it is.

CanLit time people! My boss passed me down this book while we were working together in Vancouver. Normally, I have a hard time reading these kinds of books, but it had a glossy cover and nice large margins, so I figured I could handle it. It's the story of a young black man in Ontario dealing with his mother's dementia. You can see why I might have normally hesitated! Sometimes, though, when someone random lends me a book, I'm quite motivated to read it. Can't explain it, but there it is.  This was sitting on my friend's desk when I was crashing at his secret mountain getaway, nursing a sprained ankle and moping regretfully about the plastering I wasn't able to do. The premise intrigued me. Plus, it was fairly large in print with wide margins, so I knew I could get through it before I left.

This was sitting on my friend's desk when I was crashing at his secret mountain getaway, nursing a sprained ankle and moping regretfully about the plastering I wasn't able to do. The premise intrigued me. Plus, it was fairly large in print with wide margins, so I knew I could get through it before I left. I like Walter Mosley and grab his books when they are cheap (a quarter outside of Pulp Fiction in Vancouver) but I don't follow too closely or remember the exploits of his protagonist, Easy Rawlins.

I like Walter Mosley and grab his books when they are cheap (a quarter outside of Pulp Fiction in Vancouver) but I don't follow too closely or remember the exploits of his protagonist, Easy Rawlins.  I found two more John Christopher books at Pulp Fiction when I was in Vancouver, both first edition hardbacks for $7.95. Now that I think about it, that's actually a pretty good deal, when standard used paperbacks are going for $4.95 these days.

I found two more John Christopher books at Pulp Fiction when I was in Vancouver, both first edition hardbacks for $7.95. Now that I think about it, that's actually a pretty good deal, when standard used paperbacks are going for $4.95 these days.

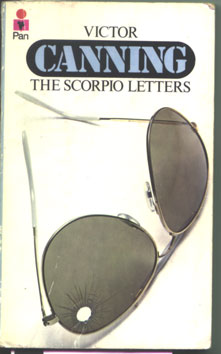

I found a great used bookstore in Vancouver (ABC books on W. Broadway near Granville, right by the bus stop). Whoever is buying books for this place knows their stuff. They had such a good and organized collection that I was drawn to some of the recommended or featured books. There was a stack of paperbacks by Victor Canning, that had cool looking covers, classic '70s and 80s British crime editions from houses like Pan. I grabbed the one with the bullet-holed aviator glasses on the cover and wasn't disappointed.

I found a great used bookstore in Vancouver (ABC books on W. Broadway near Granville, right by the bus stop). Whoever is buying books for this place knows their stuff. They had such a good and organized collection that I was drawn to some of the recommended or featured books. There was a stack of paperbacks by Victor Canning, that had cool looking covers, classic '70s and 80s British crime editions from houses like Pan. I grabbed the one with the bullet-holed aviator glasses on the cover and wasn't disappointed. The only other Theodore Sturgeon book I read,

The only other Theodore Sturgeon book I read,