This wrap-up is actually being written February 6, 2013. My extreme slow-down in reading that characterized the second half of 2012 continued on into the new year and I have had a hell of a time getting focused and getting reading and writing.

Despite the second half collapse, one has to consider 2012 another 50 books victory for Olman. I think I sensed troubled waters ahead early in the year and cranked out as much as I could. I also had the advantage of a 3-month secondment in San Francisco with a long commute and not much of a social or home life (and a mother making me dinner almost every night). But that all ended when I came back to Montreal in July and decided that I wanted to live life rather than read about it. On top of that, work got really busy and I sucessfully reproduced (with a not insignificant contribution from my wife on that score). Thus you have the graph below:

Not something I would want to take to potential investors looking to buy into a 50-book blog for 2013! Still, 67 books is my 3rd highest total since I started in 2005. Even more important, since I started, I am now averaging over 50 books a year (52.25 to be precise) which was my real goal. Now I just have to keep that going.

My highlight for 2012 was the discovery of Ursula K. Leguin. She basically kicks ass at every level a nerdy reader like me could want (great writer, genre, awesome personal politics and just super cool all around) and on top of it there is the bonus that she is a female, which whittles away ever so slightly at my hyper-masculine reading habits.

Not sure what 2013 will bring. My on-deck shelf is sagging once again. I am dedicated to cutting into that. Theme-wise, I have no special goals. I guess just consistency and another 50 books. Onward!

Monday, December 31, 2012

Saturday, December 15, 2012

67. Chinaman's Chance by Ross Thomas

First of all, I may be the proud owner of the worst cover of Chinaman's Chance (of course, Existential Ennui has the best one). I couldn't find an image anywhere on the internet, so I will assume for now that among us paperback book hunters, I'm the only one who currently has this trophy. I get into some geekiness with the cover below that I think those who have read the book may appreciate.

Chinaman's Chance is considered one of Ross Thomas' best. Once again, we get a slowly unravelling storyline which doesn't reveal itself until at least halfway through the book. In this case, two sharp dudes, Artie Wu and Quincy Durant, are renting a beach house in Malibu. Through a seeming accident, they make aquaintances with Piers Randall, an ex-software tycoon with a problem. He hires them to try and track down his missing sister-in-law, who was having an affair with a murdered senator from Pelican Bay, a seedy seaside town just under LA ("a long and grimy finger that poked itself into the backside of Los Angeles" as Thomas puts it). Things get even more complicated and interesting from there. Ultimately, the book is about Pelican Bay and how big organized crime moves into a dying town to take it over, with some help from deeply corrupt political power at the national level.

It's a thoroughly enjoyable page-turner with the usual cast of rich characters. The town of Pelican Bay is amazingly well-depicted and there are a couple of really great action moments. The plot is fairly complex, going really big picture with the backstory, but I never got lost (and I'm reading at a very slow pace these days, like a chapter a night, so that's good). Thomas is like a bartender that makes a delicious mixed drink of espionage and crime and Chinaman's Chance is like a great night at his bar.

[the rest of this review is more aimed at people who have already read the book. There aren't any major spoilers, but several references I don't bother to explain.]

This is my fourth Ross Thomas book and I think I definitely have an understanding of his style, for better and for worse. I say for better, because he is a master of many important writing skills: characterization, dialogue, spatial description and world-building (especially of towns and cities, but he also is able to create wonderful little social ecologies i a few pages, like a rundown mixed residential and commercial neighbourhood with all its key players and locations). I say worse, because he has two tendencies that rub me slightly the wrong way. They are stylistic choices and I am probably alone in not liking them. Indeed, it is quite possible that fans of his love them. The first is that I feel like he creates principal characters that are quirky for quirky's sake and both he and them are a little too proud of it. Artie Wu is a great case in point. The guy is a con artist and an ass-kicker, an orphan who may or may not be in line for the throne of China. Okay, fine, that's kind of cool and fun. But he also has a super-beautiful Scottish wife and two sets of twins! It's all a bit much and kind of unrealistic given his profession. The second thing is the sexuality in his books is pretty silly and again to this reader jarringly unrealistic. The super-rich dude who hires Wu and Durant has a super-beautiful actress/singer wife who is a nymphomaniac of the kind you only found in Penthouse letters. She also has a super-hot sister. Both throw themselves at Quincy Durant whose psychological impotence also never happened in the history of science. Ross Thomas would be the worst gynecologist ever. I get that these books are escapist fantasies, so it is perhaps pedantic of me to harp on about realism. But I just find he goes a little too far in some cases with the quirkiness and the fantasy sex objects.

I think that's why I still think the Porkchoppers is so far his masterpiece. It's a much darker book, so the quirkiness is tamped down. You get the wide range of characters and their rich backgrounds, but everybody seems quite realistic. For those of you who have read many more of his books, which ones are closer to the Porkchoppers? Don't get me wrong, I am going to continue reading his books and look forward to the continunation of the Wu and Durant saga. But I think I know what to expect now and that will make me more discerning.

Now onto the cover. What a doozy! This cover is so Dallas. It makes me think it will be one of those mainstream epic novels that "adults" read in the 70s with the embossed covers. Clearly, it targetted that audience. I wonder how well it fared. Though quite tacky ( "Oh why oh why can't I get it up?" Quincy Durant thinks, "even when a super-hot movie star strips and masturbates in front of me.), I do appreciate that a real effort was made to capture much that is actually in the book. A bunch of the characters are there. The beach house and Pelican Bay are shown. The only real innacuracy is that Tony Egg is bald and it looks like instead of making Icky Norris black, they just put him in the shadow (some editor was probably like "we've already got a chinese on the cover, if we put a black guy on the back, people will be turned off."). It's hard to see with my scan, but on the spine are two patrol cops in helmets, which I think are supposed to be Sheriff Ploughman and Lt. Lake, which is totally wrong (they are detectives and never in uniform in the book). Finally, the blowing up vehicle does not look like a motor home. No credit is given for the cover design.

Here, for your pleasure, is the cover annotated with all the characters:

Chinaman's Chance is considered one of Ross Thomas' best. Once again, we get a slowly unravelling storyline which doesn't reveal itself until at least halfway through the book. In this case, two sharp dudes, Artie Wu and Quincy Durant, are renting a beach house in Malibu. Through a seeming accident, they make aquaintances with Piers Randall, an ex-software tycoon with a problem. He hires them to try and track down his missing sister-in-law, who was having an affair with a murdered senator from Pelican Bay, a seedy seaside town just under LA ("a long and grimy finger that poked itself into the backside of Los Angeles" as Thomas puts it). Things get even more complicated and interesting from there. Ultimately, the book is about Pelican Bay and how big organized crime moves into a dying town to take it over, with some help from deeply corrupt political power at the national level.

It's a thoroughly enjoyable page-turner with the usual cast of rich characters. The town of Pelican Bay is amazingly well-depicted and there are a couple of really great action moments. The plot is fairly complex, going really big picture with the backstory, but I never got lost (and I'm reading at a very slow pace these days, like a chapter a night, so that's good). Thomas is like a bartender that makes a delicious mixed drink of espionage and crime and Chinaman's Chance is like a great night at his bar.

[the rest of this review is more aimed at people who have already read the book. There aren't any major spoilers, but several references I don't bother to explain.]

This is my fourth Ross Thomas book and I think I definitely have an understanding of his style, for better and for worse. I say for better, because he is a master of many important writing skills: characterization, dialogue, spatial description and world-building (especially of towns and cities, but he also is able to create wonderful little social ecologies i a few pages, like a rundown mixed residential and commercial neighbourhood with all its key players and locations). I say worse, because he has two tendencies that rub me slightly the wrong way. They are stylistic choices and I am probably alone in not liking them. Indeed, it is quite possible that fans of his love them. The first is that I feel like he creates principal characters that are quirky for quirky's sake and both he and them are a little too proud of it. Artie Wu is a great case in point. The guy is a con artist and an ass-kicker, an orphan who may or may not be in line for the throne of China. Okay, fine, that's kind of cool and fun. But he also has a super-beautiful Scottish wife and two sets of twins! It's all a bit much and kind of unrealistic given his profession. The second thing is the sexuality in his books is pretty silly and again to this reader jarringly unrealistic. The super-rich dude who hires Wu and Durant has a super-beautiful actress/singer wife who is a nymphomaniac of the kind you only found in Penthouse letters. She also has a super-hot sister. Both throw themselves at Quincy Durant whose psychological impotence also never happened in the history of science. Ross Thomas would be the worst gynecologist ever. I get that these books are escapist fantasies, so it is perhaps pedantic of me to harp on about realism. But I just find he goes a little too far in some cases with the quirkiness and the fantasy sex objects.

I think that's why I still think the Porkchoppers is so far his masterpiece. It's a much darker book, so the quirkiness is tamped down. You get the wide range of characters and their rich backgrounds, but everybody seems quite realistic. For those of you who have read many more of his books, which ones are closer to the Porkchoppers? Don't get me wrong, I am going to continue reading his books and look forward to the continunation of the Wu and Durant saga. But I think I know what to expect now and that will make me more discerning.

|

| Can you name all the characters? |

Now onto the cover. What a doozy! This cover is so Dallas. It makes me think it will be one of those mainstream epic novels that "adults" read in the 70s with the embossed covers. Clearly, it targetted that audience. I wonder how well it fared. Though quite tacky ( "Oh why oh why can't I get it up?" Quincy Durant thinks, "even when a super-hot movie star strips and masturbates in front of me.), I do appreciate that a real effort was made to capture much that is actually in the book. A bunch of the characters are there. The beach house and Pelican Bay are shown. The only real innacuracy is that Tony Egg is bald and it looks like instead of making Icky Norris black, they just put him in the shadow (some editor was probably like "we've already got a chinese on the cover, if we put a black guy on the back, people will be turned off."). It's hard to see with my scan, but on the spine are two patrol cops in helmets, which I think are supposed to be Sheriff Ploughman and Lt. Lake, which is totally wrong (they are detectives and never in uniform in the book). Finally, the blowing up vehicle does not look like a motor home. No credit is given for the cover design.

Here, for your pleasure, is the cover annotated with all the characters:

Friday, November 30, 2012

66. Voyage to the North Star by Peter Nichols

Dear readers, please be forewarned that I have decided it to slum it for a book and have delved into the murky gutters of literary fiction. For those of you genre fiction enthusiasts with a delicate disposition, I would recommend that you stop reading now, as this stuff is pretty lowbrow and generally frowned up by right-thinking critics. Despite its reputation, there is some very entertaining and well-written literary fiction, though from what I understand, most of it is simplistic pap, churned out to satisfy the baser appetites of an undiscriminating public of upper-middle class wives, New Yorker subscribers, liberal arts graduates and so on. I've even heard that some of the better known literary fiction authors are actually nom de plume's of succesful crime, science fiction and fantasy authors!

Here is how I took my first steps down into this mouldy basement of failed narrative dreams. As you know, I am a huge follower of the late, great John Christopher and am on a quest to find all of his work, which was written in a wide range of genres (post-apocalyptic, romance, mystery, horror and even cricket!) under at least seven different pseudonym. At least one of those names was Peter Nichols. I've recently made a list of those names that I keep in a small card in my wallet along with the other specific titles I am hunting for. Whenever I am in a bookstore, I can quickly scan through the paperback shelves to see if by chance any of them will show up. So for, no luck. I think I would do better in Great Britain.

Last week, I happened to be near the Bibliotheque Nationale. It's been a while since I've been there, but had the time to pop in. Saw a fantastic exhibit about this Polish philosopher and peace activist who ended up in Montreal after the war. The exhibhit was mainly his collection of books, which was amazing. They also had some cool intelligence documents from his role working for the British Secret Service in WWII. Anyways, I did a quick check of the english fiction section and went through hunting for al the John Christopher nom de plume's. I found nothing, but as you have probably guessed by now, I discovered this book by Peter Nichols, which is one of Christopher's pseudonyms. It's not him, but it looked pretty interesting and I got sucked in by the preface, which was a horrific little short story about a rich American industrialist on safari shocking the British hunters by machine-gunning a bunch of giraffes. So I checked it out, despite my full on-deck shelf.

Voyage to the North Star takes place at the height of the Depression. The protagonist is Will Boden, an unemployed sea captain who lost his own ship in a shameful incident. He encounters Carl Schenk, the afore-mentioned industrialist, who fashions himself a Teddy Roosevelt type. He is aggressive and reckless and loves machines and killing animals. He becomes obsessed with making a trip to the arctic to collect as many big animals and birds as he can. He hires Boden to find him a ship, but ends up going with a totally inappropriate luxury steam ship. The whole thing spells disaster from the start, but the intrigue is about how it will all go down and how everyone will react.

It's an entertaining read. The plot moves forward at a good pace, with diversions into many of the characters' backstories, that are all interesting. You know from the start that Schenk is going to do something stupid to doom them all, but the results that followed were unexpected and kept me turning the pages. I think what hangs the unfortunate "literary fiction" label around Voyage to the North Star is that, while the story is strong, it has very obvious "themes", such as the folly of the civilized white colonialist in the face of the native other, the effects of class hierarchy on human relations, the honesty of the man who works with his hands in contrast to those who manipluate capital (and other men) and of course a sprinkling of incestuous sexual abuse. I believe that this book falls under the even lower sub-category of literary fiction (if you can believe it gets any lower, but there is something for every degenerate taste out there) of "post-colonial" fiction.

So don't worry, dear reader, you won't find me anytime soon skulking in downtown coffee shops with a trade paperback or joining suburban women's reading groups. This was just a brief diversion and I shall climb back up onto honest and rigorous heights of proper reading: the crime, science fiction and fantasy genres. I can safely report, though, that at least in this case, some literary fiction is actually pretty good.

Friday, November 16, 2012

65. The Hamelin Plague by A. Bertram Chandler

I have only the vaguest memory of where I found this book, but I do recollect thinking I really shouldn't be taking it due to an overfull on-deck shelf moratorium on buying new books at the time. However, that moratorium can be temporarily put aside in the case of a few exceptions and one of the biggest exceptions is a new, obscure edition to the post-apocalyptic genre. When the apocalypse is rats destroying civilization than you have no choice.

Tim Barrett, first mate on a merchant marine ship playing the waters around Australia, comes home to a frigid post-miscarriage wife. This is his burden. More interestingly, the news on land is the increasingly aggressive behaviour of rats across Australia. This hits close to home when, in an effectively horrific scene, a neighbour's baby has a portion of its face chewed away in the crib. This incident, plus the dead dog in the street and one of his car tires being chewed off were not quite warning enough and Barrett heads back out on another run. All the men are nervous on this trip, worried about their various situations back home. The news gets worse and worse and weirder. There are unexplained fires and planes falling out of the sky. We piece together that this is more than just rats being aggressive, but a seemingly organized attack against all of humanity. There are sightings of mutant rats, that stand on their hind legs and resemble small, nasty kangaroos.

When they do come back to Sydney, the entire city is burning. Ignoring the usual protocol, they come back to port and rush off to find their loved ones. At this point, all of Australia is in total chaos. Barrett makes it back to the ship with his wife and a few crew members and they push off from the dock just in time. With limited resources and information, they become a floating outpost in a ruined world, with Barrett as their captain. Their first run-in is with a small cruise ship, led by a retired admiral. This brings a bunch of civilians on board, as well as two conflicts in the form of the admiral versus Barrett in a power struggle and the Admiral's hot and motivated young niece who does all the things Barrett's lame, depressed and bitter wife doesn't (like serving him hot tea while his wife spends the whole time sleeping in the cabin).

The Hamelin Plague has real promise, especially in the first two-thirds, but it never quite reaches its potential. There are not enough actual encounters with the rats. After the brief escape from the burning city, all the action takes place at sea and the rats are doing their damage on the land. The intra-human conflict also gets resolved quite easily, though there is a pretty good fight with some fishermen turned pirate. It's the ending that really undermines the book though, coming way too fast and easily, involving a nudist colony and the goofiest, yet thematically appropriate solution to the problem (can you guess? Hint, look at the title and think of the story it refers to). Even lamer is the way the sexual conflict for Barrett is resolved, a complete cop-out all around, where his lame wife gets motivated by the sounds of crying children on an island (where the rats were breeding them for food in another nicely horrific touch). She goes rushing off to save them and Barrett than has to save her and this rekindles their love. The young floozy, who is hot and single, easily moves on. So everybody retains their moral wholesomeness. Weak sauce, A. Bertram! But hey it kept me turning the pages.

Tim Barrett, first mate on a merchant marine ship playing the waters around Australia, comes home to a frigid post-miscarriage wife. This is his burden. More interestingly, the news on land is the increasingly aggressive behaviour of rats across Australia. This hits close to home when, in an effectively horrific scene, a neighbour's baby has a portion of its face chewed away in the crib. This incident, plus the dead dog in the street and one of his car tires being chewed off were not quite warning enough and Barrett heads back out on another run. All the men are nervous on this trip, worried about their various situations back home. The news gets worse and worse and weirder. There are unexplained fires and planes falling out of the sky. We piece together that this is more than just rats being aggressive, but a seemingly organized attack against all of humanity. There are sightings of mutant rats, that stand on their hind legs and resemble small, nasty kangaroos.

When they do come back to Sydney, the entire city is burning. Ignoring the usual protocol, they come back to port and rush off to find their loved ones. At this point, all of Australia is in total chaos. Barrett makes it back to the ship with his wife and a few crew members and they push off from the dock just in time. With limited resources and information, they become a floating outpost in a ruined world, with Barrett as their captain. Their first run-in is with a small cruise ship, led by a retired admiral. This brings a bunch of civilians on board, as well as two conflicts in the form of the admiral versus Barrett in a power struggle and the Admiral's hot and motivated young niece who does all the things Barrett's lame, depressed and bitter wife doesn't (like serving him hot tea while his wife spends the whole time sleeping in the cabin).

The Hamelin Plague has real promise, especially in the first two-thirds, but it never quite reaches its potential. There are not enough actual encounters with the rats. After the brief escape from the burning city, all the action takes place at sea and the rats are doing their damage on the land. The intra-human conflict also gets resolved quite easily, though there is a pretty good fight with some fishermen turned pirate. It's the ending that really undermines the book though, coming way too fast and easily, involving a nudist colony and the goofiest, yet thematically appropriate solution to the problem (can you guess? Hint, look at the title and think of the story it refers to). Even lamer is the way the sexual conflict for Barrett is resolved, a complete cop-out all around, where his lame wife gets motivated by the sounds of crying children on an island (where the rats were breeding them for food in another nicely horrific touch). She goes rushing off to save them and Barrett than has to save her and this rekindles their love. The young floozy, who is hot and single, easily moves on. So everybody retains their moral wholesomeness. Weak sauce, A. Bertram! But hey it kept me turning the pages.

Sunday, October 28, 2012

64. The Frog in the Moonflower by Ivor Drummond

|

| it is a cool cover, no? |

I should have listened to my inner skepticism. There are some really good moments, but overall it was very unsatisfying. This book suffers from an awkward structure and an assumed familiarity with the "famous team" that really isn't all that interesting. They are very upper class and seem to have a ton of different skills. It is in the action moments when they use these skills, particularly in an exciting car grabbing scene and another B&E, that the book is very enjoyable. But the rest of it is kind of a mess, wallowing in annoying upper-class self-satisfaction with no intrigue and a muddy sense of who is bad. So not great. Too bad, as I thought I had found a nice little discovery there. Turns out Drummond is a pseudonym for Roger Longrigg, a prolific and successful British author who wrote under many different names.

Sunday, October 21, 2012

63. The Gabriel Hounds by Mary Stewart

Talk about a drop-off! I went from crushing several books a week to reading almost nothing for 3 months. Here's what happened. I went from staying in a garage above my parents in California on a work assignment where I had an hour on public transit a day, plus lots of alone quiet time in a region that for whatever reason really makes on want to read to a busy, hot summer in Montreal where when I wasn't working or socializing I wanted to be outside either working on projects or walking the neighbour's dog. On top of that, I was overseeing the biggest project of all, helping my wife to bring in a new future reader into the world. Despite all that, I could have read a bit more in some spare quiet moments like just before going to sleep (or more realistically, in the bathroom). The final killer on my reading was that I inherited my wife's old iPad, which is the ultimate attention-span killer. I also think I allowed myself to let up because I had already reached my quota. I am slowly feeling the urge to read to come back, but I make no promises. It's basketball season!

On Labour Day weekend, my wife and I drove to cottage country in Ontario. Rather than take the main highway to Toronto and then up to the Georgian Bay, we decided to go through Ottawa. It's a slightly slower route, but much more scenic. Near the end, somewhere around the Kawartha's, in what was a mix of farm and vacation country, on an old two-lane highway, we saw a sign for "The World's Smallest Bookstore". Though a bit behind schedule, I had to stop. It turned out to be a small hobby farm with a trailer that was filled with bookshelves. Nobody was around but the squawking chickens in the coops next door. You basically took whichever books you wanted and left $3 for each one. They also sold eggs in the same manner, but the mini-fridge was empty. It was a very cool set-up and really got me excited. There were tons of old hardbacks. Unfortunately, the fiction was almost all Book Club editions of bestsellers from the 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s, lots of bestsellers and obscure but mainstream novels that looked kind of bland. (Personally, I have no problem with Book Club editions, as they can often look just as nice as originals and sometimes have alternative designs with neat little tidbits.) I did find this Mary Stewart book as well as the first three Eric Amblers. So no major treasure, but a fun little discovery.

The Gabriel Hounds is one of her classic gothic thrillers. It's the story of a plucky young aristocratic woman on bus tour holiday in London. She runs into her favourite cousin, who has grown into a dashing young man. They share an eccentric aunt who fled to the middle east years before and had grown into a kind of crazy legend in the family and locally, as she took over an old Arabian Nights style castle. Both cousins had planned on paying her a visit, but because of unseen circumstances, our heroine goes first. She quickly finds things very suspicious in the compound, where Great-Aunt Harriet at first refuses to see her, communicated via a suspicious British man who claims to be taking care of her. Things get weird, adventure ensues (actually some pretty lively stuff compared to her last gothic thriller that I read), the two cousins realize they love each other (they are distant cousins, though the constant incest subtext is definitely weird) and papa shows up to whisk them back to their hotel rooms to get cleaned up and have some tea.

Again, her gothic thrillers are all slightly mild. The bad stuff going on isn't all that bad and you never feel that the protagonist is truly threatened. This one did have a really cool location, Dar Ibrahim, the aunt's compound, once a thriving castle for the local emir and now all rundown, with secret doors, an indoor pond and menagerie and all decorated with rotting, decaying furnishings of past arabic glory. And there was some pretty good violence (though none of it directed at the protagonist). I think I got a good taste for these kinds of books of hers and probably won't read any more (unless someone can recommend a particularly good one, on par with her Arthurian stuff). They are good, but not quite my cup of tea.

On Labour Day weekend, my wife and I drove to cottage country in Ontario. Rather than take the main highway to Toronto and then up to the Georgian Bay, we decided to go through Ottawa. It's a slightly slower route, but much more scenic. Near the end, somewhere around the Kawartha's, in what was a mix of farm and vacation country, on an old two-lane highway, we saw a sign for "The World's Smallest Bookstore". Though a bit behind schedule, I had to stop. It turned out to be a small hobby farm with a trailer that was filled with bookshelves. Nobody was around but the squawking chickens in the coops next door. You basically took whichever books you wanted and left $3 for each one. They also sold eggs in the same manner, but the mini-fridge was empty. It was a very cool set-up and really got me excited. There were tons of old hardbacks. Unfortunately, the fiction was almost all Book Club editions of bestsellers from the 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s, lots of bestsellers and obscure but mainstream novels that looked kind of bland. (Personally, I have no problem with Book Club editions, as they can often look just as nice as originals and sometimes have alternative designs with neat little tidbits.) I did find this Mary Stewart book as well as the first three Eric Amblers. So no major treasure, but a fun little discovery.

The Gabriel Hounds is one of her classic gothic thrillers. It's the story of a plucky young aristocratic woman on bus tour holiday in London. She runs into her favourite cousin, who has grown into a dashing young man. They share an eccentric aunt who fled to the middle east years before and had grown into a kind of crazy legend in the family and locally, as she took over an old Arabian Nights style castle. Both cousins had planned on paying her a visit, but because of unseen circumstances, our heroine goes first. She quickly finds things very suspicious in the compound, where Great-Aunt Harriet at first refuses to see her, communicated via a suspicious British man who claims to be taking care of her. Things get weird, adventure ensues (actually some pretty lively stuff compared to her last gothic thriller that I read), the two cousins realize they love each other (they are distant cousins, though the constant incest subtext is definitely weird) and papa shows up to whisk them back to their hotel rooms to get cleaned up and have some tea.

Again, her gothic thrillers are all slightly mild. The bad stuff going on isn't all that bad and you never feel that the protagonist is truly threatened. This one did have a really cool location, Dar Ibrahim, the aunt's compound, once a thriving castle for the local emir and now all rundown, with secret doors, an indoor pond and menagerie and all decorated with rotting, decaying furnishings of past arabic glory. And there was some pretty good violence (though none of it directed at the protagonist). I think I got a good taste for these kinds of books of hers and probably won't read any more (unless someone can recommend a particularly good one, on par with her Arthurian stuff). They are good, but not quite my cup of tea.

Monday, August 27, 2012

62. Dans la peau de Bernard by Guy Lavigne with illustrations by Réal Godbout

Well this an abrupt change of pace. I went from near-constant reading and completion of books to an almost total cessation of any reading at all! This young adult book from Québec really is the only book I've completed since I got back from my trip to California. I came back to a beautiful Montreal summer and a ton of responsibilities at home and at work. On top of it, I'm just not feeling really able to concentrate on a book when I do have a few moments before bed to read. So there it is, good thing I already made my 50 books this year. I did have a trip to Toronto and during the train ride there managed to finish Dans la peau de Bernard (the french only capitalize the first word in titles).

A co-worker of my wife's lent it to her and she was slowly working on it to try and improve her french. It's all about a boy who moves to Montreal and spends all his time wandering around the alleys of Montreal. That is also a pastime I enjoy. Furthermore, it has illustrations by Réal Godbout, who is a seminal cartoonist in Quebec for his work in Croc magazine (sort of like Mad Magazine) and his character Michel Risque and Red Ketchup (check out this english summary of one of the Red Ketchups to see his anarchic style, it's such great stuff). I love his thick-lines, energy and counter-culture attitude. Here, the frenetic energy of his characters is brought into a more realistic mode (for the most part) and he does a wonderful job of capturing Montreal in the summer. For some reason, the entire book is scanned into Google Books, so you can scroll through it and see the illustrations if you'd like.

The story is about Bernard, a young boy whose parents move from a big house in the suburbs to an apartment in the Plateau. Both parents had lost their jobs and the uncle got the dad one working at a Depanneur (corner store) I guess it takes place in the 70s or early 80s, a time when this neighbourhood was much more working class and such a move seen as a big step downward economically. Today, affluent, urban couples are bidding top dollar for such an apartment. Both parents are profoundly (and selfishly) depressed. At home, they fight and then the mother goes to her room to cry and the father passes out on the easy chair after downing several big beers. Bernard is neglected and spends his days exploring the alleys of the Plateau. It's pretty sad and seems kind of realistic. His time outside of the home is quite rich. He is a child open to the beauty of his environment (in contrast again to his broken and inward-looking parents). He gets involved in some scrapes in an attempt to get up on roofs to get a better view. Things start to get really interesting when he meets an eccentric old lady whom he spied on making her way down an alley going through garbage cans. I really can't say much more beyond that this book totally surprised me, going in a direction I had not expected at all. It sticks with its theme of parental neglect, but in a pretty crazy way. Great book. I wish it would be translated into english, because it is kind of a classic. If you are francophone or have kids in french immersion, pick this one up.

Friday, July 27, 2012

on-deck shelf update July 2012

My on-deck shelf is on top of my chest of drawers. It has quite a few large non-fiction hardback books on the right hand side that I rarely make a dent in. All the real activity is the paperbacks running from there to the left, where I grab the next book. Before I left for California in April, the on-deck shelf had gotten so out of control that it was two layers deep! This is bad and I put out a full embargo on any new book purchases until I could get it under control. Thanks to my isolation, two-hour commute and lack of internet, I was able to work that on-deck shelf way down, eliminating that ungainly second row entirely and digging deep into the paperbacks on the main row. I also, however, started buying books again. What I had really been hoping for was to read so many of the paperbacks that I would be forced to get into the hardbacks, but there was just too many good finds in California and I'm just going to have to read some more awesome fiction paperbacks for a while.

Happily, though, that whole section is almost entirely refreshed and I've got nothing but new books in the paperback section, all of which I'm pretty eager to read. It's a nice feeling to refresh the on-deck shelf. Sometimes there are books that you keep putting off and keep putting off and they get a kind of staleness, through no fault of their own, that impedes you from possibly ever reading them. That can put a real blockade on your on-deck shelf and you need something like a 3-month trip to California to break through it.

Here's what I'm looking at now:

I am not complaining at all. Au contraire, I fall to my knees and offer a prayer to Librus, the god of the book, and his demigods and nymphs who have guided me so benevolently this year. Onward!

Thursday, July 26, 2012

61. The Murder of Miranda by Margaret Millar

The Murder of Miranda is one of Millar's later books. I found a well-read library hardback in the Maritimes, notable for a cool picture of the author on the back with her 3-month old Newfoundland (the dog, not a real Newfie that she imported for her pleasure). She looks like a pleasant, older lady next door except for a certain tightness around the mouth and an intelligence in the eyes that one would expect from someone who has peered into the darkness and weakness of men's souls and not turned away.

In the Murder of Miranda we have more darkness and weakness, especially weakness. Everybody is broken, flailing around in life, desperately grabbing what weird pleasure their twisted hearts allow them. The story takes place in and around a private beach club in San Felice on the central Californian coast. Miranda Shaw is the attractive but aging wife of an old millionaire. She is obsessed with preserving her beauty. When her husband dies, she expects to become a wealthy widow. She takes up with the young, handsome life guard. There are many other storylines and characters circling around hers: the club administration made up of the burnt out manager and his efficient but jealous assistant (also seduced by the life guard), the poison pen writer Mr. Van Eyck, his wealthy sister who is married to a retired naval officer and has two full-grown but weirdly childlike daughters and finally the juvenile delinquent who longs for attention from the life guard while he makes life hell for everyone else in the club. The whole thing is anchored more or less by junior lawyer Tom Aragon, who is responsible for overseeing Miranda Shaw's estate. Part of that responsibility is finding her and telling her that her husband actually died in total bankruptcy and that she would not be receiving anything.

Where does the murder of Miranda come in? Well you'll just have to read and find out. Suffice it to say that this is not a conventional mystery story. Millar plays with the structure here in a way that had me a bit befuddled until the end where I would have laughed out loud with the cleverness except that it was just so bleak and nasty. This one reminded me a lot of Vanish in an Instant, where the investigator was also a young lawyer moving among a tangled nest of crazy, broken people. Here, though, we aren't distracted by an arbitrary love. Aragon is married and faithful, but his wife is off getting a degree for a year. This allows him to remain even more disinterested in the case. You don't find out much about Tom Aragon, he doesn't wax philosophical and barely even gets involved beyond just finding people and talking to them. I found there was a certain absence of a protagonist because of that, but it does allow for a more objective view onto the flaws of humanity.

In the Murder of Miranda we have more darkness and weakness, especially weakness. Everybody is broken, flailing around in life, desperately grabbing what weird pleasure their twisted hearts allow them. The story takes place in and around a private beach club in San Felice on the central Californian coast. Miranda Shaw is the attractive but aging wife of an old millionaire. She is obsessed with preserving her beauty. When her husband dies, she expects to become a wealthy widow. She takes up with the young, handsome life guard. There are many other storylines and characters circling around hers: the club administration made up of the burnt out manager and his efficient but jealous assistant (also seduced by the life guard), the poison pen writer Mr. Van Eyck, his wealthy sister who is married to a retired naval officer and has two full-grown but weirdly childlike daughters and finally the juvenile delinquent who longs for attention from the life guard while he makes life hell for everyone else in the club. The whole thing is anchored more or less by junior lawyer Tom Aragon, who is responsible for overseeing Miranda Shaw's estate. Part of that responsibility is finding her and telling her that her husband actually died in total bankruptcy and that she would not be receiving anything.

Where does the murder of Miranda come in? Well you'll just have to read and find out. Suffice it to say that this is not a conventional mystery story. Millar plays with the structure here in a way that had me a bit befuddled until the end where I would have laughed out loud with the cleverness except that it was just so bleak and nasty. This one reminded me a lot of Vanish in an Instant, where the investigator was also a young lawyer moving among a tangled nest of crazy, broken people. Here, though, we aren't distracted by an arbitrary love. Aragon is married and faithful, but his wife is off getting a degree for a year. This allows him to remain even more disinterested in the case. You don't find out much about Tom Aragon, he doesn't wax philosophical and barely even gets involved beyond just finding people and talking to them. I found there was a certain absence of a protagonist because of that, but it does allow for a more objective view onto the flaws of humanity.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

60. The Long Dark Night by Joseph Hayes

One more sign that I am truly blessed is that Dark Carnival, one of the better sci-fi, fantasy and mystery bookstores in North America, is literally a block and a half from my parents's house. It's kind of insane and became a regular haunt for me during my 3 months in California. If I got back from work early enough, I would often park my bike outside and lurk in the back room where the used books are. The store is overstocked, with new books stacked on the floor (though stacked somewhat neatly). The back section was quite a mess, with bottom shelves of used books being inaccessible due to piles of books and toys. But slowly over the summer, one of the employees was hitting it hard, working on cleaning it up and near the end of my trip the back section got in better and better order until I could actually reach the bottom shelves (one of which carried the letter C where I was desperately hoping to stumble upon a lost John Christopher; no such luck). I did find this Joseph Hayes book, which I had never heard about before, but which had a very intriguing premise: a young man falsely accused of rape in a small New England town plots his brutal revenge against the entire town. It was written in 74 and the paperback was published in best-seller rather than a crime or mystery format. There is rape mentioned in the blurb and a lot of other sensational stuff, so it could have gone either way and perhaps just been a lurid titillating mass market book. However, I know of Joseph Hayes having read The Desperate Hours and really enjoying it. That was written 2 decades earlier, but the initial prose seemed solid, so I picked it up.

Turns out to have been a good choice. This book is definitely hardcore and even has some situations that would put it well into the lurid category. However, they are all done off-camera and referred to rather than spread out before the reader's eyes. The story is great. A young, poor hard-working student, Boyd Ritchie, comes from the midwest to this patrician New England town on a scholarship. He's there for half a school year before he gets mixed up with the town beauty, who is betrothed to the town scion, but who also is a big slut. A situation happens where the girl accuses Boyd of rape to protect her own reputation. He gets caught, brutalized by the sociopathic chief of police (an ex-Texas Ranger, disgraced for killing a suspect in his old job), then convinced to plea bargain and then screwed over by the judge. In prison, he gets further brutalized and something snaps, so that he spends the rest of the time planning his revenge on the entire town. The book is the entire night of his revenge.

This is good, gripping, nasty stuff. The plan is complex and seeing its execution, while learning through flashbacks and the ensuing investigation how he prepared for it is really enjoyable. Watching it (and Boyd himself) unravel while the "good" guys start to figure out what is going on is also a great pleasure. This is one of those books that is perfect for a long plane ride, easy to digest, with lots of short segments jumping from character to character. The last third goes on a bit long as we get slightly bogged down in some family relationships (and how the crisis tests marriages and childrens' love for their parents) . Overall, though, a great summer thriller read.

Friday, July 20, 2012

59. Thrilling Cities by Ian Fleming

Thrilling Cities is another collection of Fleming's columns written for the Sunday Times. For this series, he was sent on two trips around the world to write about the racier sides of various cities. The first trip is to Asia and across the Pacific to the US and the second is a drive across Europe.

It's a really entertaining read. He is a fun writer and it is cool to see both the state of these various cities in the early 60s and the cultural approach that this semi-upper class Brit takes to them. The first half, especially the Asian part, seems a lot more fun, because Fleming was single (or at least had left his wife behind). In the drive across Europe, she is with him (though barely mentioned) and we hear very little about any dancing girls or geishas.

What was interesting is that he absolutely hated New York. The way he wrote about it made it sound like the NYC of Death Wish except the people are even ruder. My father worked in New York for a summer around this time and he had a very similar reaction. Fleming hated it so much that he even adds a little James Bond vignette where he goes on one of his high-class consumer fetish trips (trying to get this razor and that shirt and so on; Bond is kind of boring when he gets into this stuff, though it may have been extra-exaggerated for effect here) and ends up having none of it work out.

This book is also written around the time of the beginning of the Parker series and what Fleming writes about the syndicate in the Chicago chapter very much jibes with the world Westlake describes in The Outfit. I think any Parker fan will enjoy Thrilling Cities, at the very least for the U.S. section.

It's a really entertaining read. He is a fun writer and it is cool to see both the state of these various cities in the early 60s and the cultural approach that this semi-upper class Brit takes to them. The first half, especially the Asian part, seems a lot more fun, because Fleming was single (or at least had left his wife behind). In the drive across Europe, she is with him (though barely mentioned) and we hear very little about any dancing girls or geishas.

What was interesting is that he absolutely hated New York. The way he wrote about it made it sound like the NYC of Death Wish except the people are even ruder. My father worked in New York for a summer around this time and he had a very similar reaction. Fleming hated it so much that he even adds a little James Bond vignette where he goes on one of his high-class consumer fetish trips (trying to get this razor and that shirt and so on; Bond is kind of boring when he gets into this stuff, though it may have been extra-exaggerated for effect here) and ends up having none of it work out.

This book is also written around the time of the beginning of the Parker series and what Fleming writes about the syndicate in the Chicago chapter very much jibes with the world Westlake describes in The Outfit. I think any Parker fan will enjoy Thrilling Cities, at the very least for the U.S. section.

Saturday, July 14, 2012

interlude: Kayo Books in San Francisco

|

| SCHWING! |

I cannot understand how I could have only heard of this place a week ago. It's been in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco for 17 years. I finally got a chance to sneak out from work last Thursday and had about an hour to spend. Oh my god. This place is the paperback collector's nirvana. I could have come here every day just to browse. The stock is incredible. But it's not only the volume and diversity (which I'll get into), but the organization and cleanliness. While I enjoy the anticipation of the hunt while digging through dusty piles, I'll also never understand why most used bookstore owners cannot organize their stock. This place shows how it should be done. There is a section for everything and within those sections, it is all arranged in meticulous alphabetical order. Every shelf is easily approachable, with lots of space so you can take your time to scan the rows. You can see these lovely shelves in the picture above. The sections are great, as well. There are mysteries and hard-boiled as well as a great science fiction section (though very limited fantasy) and then tons of sub-sections, especially with the erotic paperbacks, it breaks down to things like Juvenile Delinquents, Biker Gangs, Catholic Schools, Pregnancy Scares, etc.

Interestingly, there were only two Richard Starks, but the proprietor (the wife of a husband and wife team; super friendly, helpful and knowledgeable) told me that Stark was in constant demand ever since they opened the store. They also had an insane Peter Rabe collection, more books than I even knew he had written. They were up in the $10-15 range, a bit rich for my blood, but I got one of the cheaper ones. One dissapointment was that they had no Margaret Millar, which surprised the proprietor as well. But did I score! Check out my loot below:

|

| Excuse the poor lighting. |

That Night Cry by William Stuart I've been looking for for years, ever since August West made it sound so good. What a gorgeous cover! I already have The Little People in hardback, but I couldn't resist the awesome paperback with this cover in such good condition. It's My Funeral is the Peter Rabe I picked up. And check it out, the original Harlequin version of The Body on Mount Royal (part of the recently reprinted series of Montreal pulp from Vehicule Press). And then I rounded it out with an early Donald Hamilton and another installment in the Operation Hang Ten series. The whole package set me back $23 and she even gave me those little plastic paperback book protectors.

Finally, the store has an awesome dog, a big friendly black lab who every ten minutes or so makes her rounds, going from customer to customer, getting some pets or just standing next to you while you peruse. So you pretty much have to put a visit to Kayo Books on your list of things you must do in your life.

Friday, July 13, 2012

58. The Weathermonger by Peter Dickinson (book 3 of the Changes trilogy)

The Weathermonger was actually the first book written. I haven't looked into it, but I think after its success, Dickinson was encouraged to go back and write some more taking place in this world. I think in some ways, this is the best of the three. The story here takes place about a year after Heartsease (about 6 years after the Changes happened). It starts in medias res with a boy and his younger sister stranded on a little rock while the tide comes in and a gang of villagers are standing on the shore line, rocks in hand, to ensure that they drown. The boy has no memory of what happened, but the girl slowly fills him (and the reader) in. He's a weathermonger, a local magician responsible for ensuring good weather for the village. He got too greedy and they decided to take him down. He lost his memory due to a blow to the head. However, losing his memory brought back his understanding of the world before the Changes. He and his sister then plan to escape. I won't go into any more plot details beyond saying that they do escape and then are sent back, to try and figure out the source of the Changes.

The first half of The Weathermonger has a similar trajectory as the first two books in the series, an adventurous journey with children in charge. It's the second half, when they meet the weathermonger and start to unravel his mystery, that takes this book to a higher plane. It's fantastical and really enjoyable. Very cool stuff and I can see now why as a kid I snuck and read ahead to find out what happened. The whole series is great, but I think the Weathermonger really stands alone as well. If you only want to read one of them, this is the one.

The first half of The Weathermonger has a similar trajectory as the first two books in the series, an adventurous journey with children in charge. It's the second half, when they meet the weathermonger and start to unravel his mystery, that takes this book to a higher plane. It's fantastical and really enjoyable. Very cool stuff and I can see now why as a kid I snuck and read ahead to find out what happened. The whole series is great, but I think the Weathermonger really stands alone as well. If you only want to read one of them, this is the one.

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

57. Heartsease by Peter Dickinson (part II of the Changes trilogy)

|

| Again, a beautiful edition that I don't have. |

The book starts in medias res, with Margaret poking around after a stoning of a witch. She notices that the stones are moving and with the help of her cousin they end up rescuing the witch, who turns out to be an American airman, sent over to investigate what happened to England and report back. He was trying to send signals from his wireless device when the village discovered him.

The rest of the book is the children trying to heal him back to health and figure out how to help him escape. All the while, we are slowly shown the nature of the village and the fear that dominates it. People affected by the changes have varying abilities to sniff out technology and the de facto village leader is a classic small-minded, sneaky and suspicious little tyrant. He keeps coming back to Margaret's farm, suspecting something is up and sensing evil around. Every now and then he also ignites the townsfolk to go on a witch hunt. At one point, they kill a bird with a broken wing because they think it is the escaped witch.

Dickinson does a great job of portraying the small, fearful minds of the close-minded rural. Here there is a concrete explanation for their behaviour, the Changes have done something to their minds. And the children go to pains to try and excuse the nastiness (and you sense Dickinson behind them trying to remind us that these people are still human beings as well). However, it really does feel like a condemnation of that kind of irrational, fearful thinking that leads so quickly to violence that we see in so many places in the world (I couldn't help but think of the American far right and their fear of so much in the world). When you are reading this, you really hate those people! He does a great job of creating tension. The last half is a super-exciting escape.

These books are short and thrilling. I would have liked just a bit more exploration of England after the Changes. There are lots of cool hints, like dog packs and blackened cities, but as a nerd, I like a bit more world-building. Overall, though, another great chapter in this trilogy.

Monday, July 09, 2012

56. The Devil's Children by Peter Dickinson (part I of The Changes Trilogy)

|

| I do not have this copy, but I want it. |

This trilogy should definitely be on the great PA book list (whereever that is). The apocalypse here is called The Change and it manifests itself quite suddenly in Great Britain causing almost everybody to suddenly hate all machines. They just go beserk and attack any kind of machine. The chaos (which we only hear of obliquely in the child narrator's memory) ends quickly, leaving the population much diminished (many dead or fled). Most people who remain still hate machines to such a degree that they can't even say words like 'tractor' or 'electricity' and going near things like downed power-lines causes them to feel totally freaked-out. They also have weird gaps in their memory where they can't remember much about history or geography. We learn later that this phenomenon seems isolated to Great Britain.

The story here is about 12-year old Nicola, who was separated from her parents during the Change. She waits for two days and then decides to make her way home. She succeeds in doing that, but nobody is left. She waits at home and one day a troupe of Sikhs come by. She ends up joining with them. For some reason, they haven't been affected by the change. They were a community of Indian immigrants who lived all in the same neighbourhood (and are mostly from the same extended family) who decided to leave the city and try and find a place to survive. They are a cool group for a post-apocalyptic setting. They have a range of skills (metalworking, agriculture, sword fighting) from their own rural backgrounds and a kind of cultural democracy, though there is a matriarch. Being immigrants and outsiders from British society already, they have a wary approach to other people already. They are wary of Nicola at first, but then realize that she can act as a sort of canary in a coal mine, feeling the aversion to technology where they don't. They want to use tools but also don't want to attract any crazed people towards them.

They do find a good place to try and make a new home from. The book is about them doing that and their interactions with the suspicious village nearby, who call them The Devil's Children. With the Change and the reversion to a pre-industrial society, comes also the old, now-modified, superstitions. I'm very curious to see where this will go. This book, in and of itself, is a neat little story about a self-sufficient young girl who falls in with these neat people and they all try and make a go of it. It is short, though, and very local in scale. It almost feels like a novella, but I guess that's because it's a young adult book. I'm glad there are two more books to go!

|

| This is the version I have and the image is kind of awesome, though I believe it refers to only The Weathermonger, the final book in the trilogy. |

Sunday, July 08, 2012

55. The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. LeGuin

Urusla K. does it again. Man, she does not play. I would say that this book, along with the Earthsea books and The Left Hand of Darkness are her best-known works. I point that out because I'm impressed how all 3 are so different and have such different styles. They share some themes (the abuse of power, exploration of human relations) and some motifs (environmental degradation) and you can hear her voice in all of them. But these are three very different books.

The Lathe of Heaven feels like classic silver age sci-fi. It almost could have been written by Philip K. Dick (except that the cohesion holds through to the end here). It feels very modern and future sci-fi (where the Earthsea are true fantasy, almost lyrical and The Left Hand of Darkness is much more of epic other world sci-fi). It's just so impressive how she can write such different books, but all of them be really good.

The story here starts out in Portland, Oregon in a mildly dystopic near-future. The environment is bad, the economy is poor and society is less free. George Orr gets arrested for using someone else's PharmCard. He's buying drugs to stop himself from dreaming. Because it's his first offense, he's sent to see a psychiatrist, who is also a dream expert. Orr doesn't want to dream, because when he does, his dreams change reality. The psyciatrist is at first interested and then when he realizes reality really is being changed, he starts trying to manipulate and harness Orr's unwanted ability. Things get crazy.

The book progresses in a series of reality shifts, each one getting slightly worse than the last. In a way, it is like a novel-length version of The Monkey's Paw. Each dream request that the doctor tries to get Orr to dream about, ostensibly for the betterment of mankind, has unexpected results, either as filtered through Orr's personality or just because that's the way the world works.

There is a lot going on in this book. Humanity does not come off well. It deals with life's purpose, morality and power. The philosophical stuff is thought-provoking, but also, as always (at least so far) with Le Guin, deftly and subtly done. The multiple futures are awesome fun. We really get multiple disaster and apocalyptic scenarios as well as giant social experiments (what happens if we get rid of race?). I lived in Portland for four years and though it's been a while, it was still cool to read all the specific changes it goes through. Mt. Hood really gets the treatment. Interesting that this book was written a decade before Mt. St. Helens blew her top!

Awesome book, super-entertaining, quick, lively and intelligent read. There is a reason it is a classic. Check it out.

Thursday, July 05, 2012

54. Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini

My dad actually pulled this one out from the fiction shelf and told me that he and my mom had both read it when they were young, that it was a great favourite back then. It looked like the kind of swashbuckling romantic adventure that I myself quite enjoy (and it was $2) so I purchased it.

It's the story of a young man adopted into a noble, rural household in Brittany who comes of age just before the French Revolution. Though he is well-raised, because he is a godson, he does not actually accrue the benefits of the family that cared for him and he seeks his fortune in law. He himself is quite removed from the emotional fervour catching among his peers until his best friend is killed in a maliciously arranged duel by a cruel count. He swears revenge on this count and in doing so, ends up taking the side of the Republic. This springs him into a series of adventures, where he becomes an actor with a travelling theatre troupe, then a fencing master and finally a politician himself. It's partly a bildungsroman, but it is also a romance and the plot, while it wanders, always pulls itself back to his feud with the count.

It's a thoroughly fun read, very satisfying. I love these books where honour and manners play an important role. People in this world behave with certain levels of courtesy whether they are good or evil and it makes for such great interchanges and verbal conflicts.

What was also interesting about this book was the pacing. It is adventurous and swashbuckling, but there is also a long section dealing with him slowly improving in the theatre, gaining more and more authority in the troupe until he finally comes in conflict with the troupe leader. These parts are not full of action, but somehow they are very satisfying and you really are caught up in the story. It was written in 1921 and was not considered high literature, even a bit low (my mother was upbraided by her teacher when she chose it for a book report in grade 11). Reading it reminds me that a book can be gripping and thrilling without having tons of physical action and conflict.

The backdrop of the French Revolution is also a great setting for this kind of adventure. You have the combination of impending chaos with fearful authority, so that there is always danger but also always a chance of escape.

I see that Sabatini wrote several other adventure novels, such as The Sea Hawk and Captain Blood. Sigh, one more author to add to my list...

It's the story of a young man adopted into a noble, rural household in Brittany who comes of age just before the French Revolution. Though he is well-raised, because he is a godson, he does not actually accrue the benefits of the family that cared for him and he seeks his fortune in law. He himself is quite removed from the emotional fervour catching among his peers until his best friend is killed in a maliciously arranged duel by a cruel count. He swears revenge on this count and in doing so, ends up taking the side of the Republic. This springs him into a series of adventures, where he becomes an actor with a travelling theatre troupe, then a fencing master and finally a politician himself. It's partly a bildungsroman, but it is also a romance and the plot, while it wanders, always pulls itself back to his feud with the count.

It's a thoroughly fun read, very satisfying. I love these books where honour and manners play an important role. People in this world behave with certain levels of courtesy whether they are good or evil and it makes for such great interchanges and verbal conflicts.

What was also interesting about this book was the pacing. It is adventurous and swashbuckling, but there is also a long section dealing with him slowly improving in the theatre, gaining more and more authority in the troupe until he finally comes in conflict with the troupe leader. These parts are not full of action, but somehow they are very satisfying and you really are caught up in the story. It was written in 1921 and was not considered high literature, even a bit low (my mother was upbraided by her teacher when she chose it for a book report in grade 11). Reading it reminds me that a book can be gripping and thrilling without having tons of physical action and conflict.

The backdrop of the French Revolution is also a great setting for this kind of adventure. You have the combination of impending chaos with fearful authority, so that there is always danger but also always a chance of escape.

I see that Sabatini wrote several other adventure novels, such as The Sea Hawk and Captain Blood. Sigh, one more author to add to my list...

Sunday, July 01, 2012

53. The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

My wife is a big Shirley Jackson fan and has several of her books. I've been meaning to give her a try for a while now and finally got motivated since it was chosen as the July read for an online book discussion group I am in. Great choice!

The Haunting of Hill House is not the first haunted house story, but it's an early one and was quite well-respected when it came out (she also wrote the short story "The Lottery" that a lot of us read in junior high). At least two movies have been made from it. It's the story of a doctor of the paranormal who gets the opportunity to study an abandoned manor in the Britsh countryside. He invites four people, whose existence have come to his attention for their own histories of being involved in some kind of paranormal activity. One of them, Eleanor, is the character through whose viewpoint the reader follows the proceedings. She lives with her sister's family and up until recently, devoted her life to taking care of her cruel, sickly mother. For her, this "experiment" is an exciting opportunity to make a break from her old life. Things do not go well.

It's a subtle, cleverly-written book. Right away, Jackson is totally direct about how foreboding and ominous the house is. She doesn't actually describe it much. Rather, she describes how it makes Eleanor feel and allows the dialogue of the others to describe what it does to them. It is freaky, and in some creative ways too, that I won't give away. It's a slow burn after that, though. We spend a lot of time learning about the doctor and the guests, the history of the house and its geography. It takes a while for things to get weird, but they do.

There is very little objective third-person description in this book, to the point that at times I didn't realize that certain people were present in a scene until they spoke. It was odd at first, until I got that we really are seeing things through Eleanor's eyes and that, as she falls under the influence of the house (if that is indeed what happens), she becomes one of those unreliable narrators.

It's a dark, nasty book. She does a great job of writing catty, underhanded, passive-aggressive dialogue. I didn't realize she was American at first, because the book takes place in England. Her prose is strong, with longer sentences, but they are very linear and lack some of the more intricately structured phrasing that I like in my British authors. And scary, I don't know how it will affect others, but I wasn't scared at all for almost the first two-thirds but then one thing happened and I was reading it in my room alone, with only one light on and I really got quite scared, to the point that I had to will myself to go down the stairs to the front door and make sure it was locked! So, your mileage may vary, but I got a serious chill from this book. I'll definitely add Shirley Jackson to my list.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

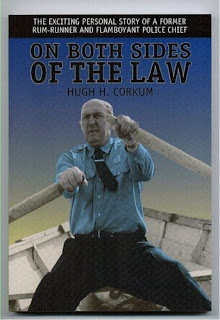

52. On Both Sides of the Law by Hugh H. Corkum

I bought this book at the Maritime museum in Lunenberg, Nova Scotia. It's one of those books that you can only get in the place it was written. The author was a rum-runner in the 30s and then became the chief of police of Lunenburg, which is the symbolic heart and soul of Canada's fishing and maritime history. This book was plainly told, but full of great anecdotes, life lessons and viewings into what life was like in this region in the middle of the twentieth century.

I bought this book at the Maritime museum in Lunenberg, Nova Scotia. It's one of those books that you can only get in the place it was written. The author was a rum-runner in the 30s and then became the chief of police of Lunenburg, which is the symbolic heart and soul of Canada's fishing and maritime history. This book was plainly told, but full of great anecdotes, life lessons and viewings into what life was like in this region in the middle of the twentieth century.Good stuff.

Monday, June 25, 2012

51. Vanish in an Instant by Margaret Millar

This is an earlier Margaret Millar, a pretty classic hardboiled whodunnit filled with all the pathetic, unsavoury, desperate characters a reader could want. In this one, the "detective" is a lawyer hired by the financially comfortable mother of the accused. The book, though has a semi-omniscient viewpoint and though the lawyer, Meecham, leads the investigation, we spend a lot of time in many of the other characters' heads. The daughter, married to a sensible doctor husband, is not sensible herself and was found passed out drunk, covered in blood in the cabin of a married man who was known in town to be a playboy. The married man is in the cabin also. Somebody stuck him in the neck several times with a kitchen knife.

This is an earlier Margaret Millar, a pretty classic hardboiled whodunnit filled with all the pathetic, unsavoury, desperate characters a reader could want. In this one, the "detective" is a lawyer hired by the financially comfortable mother of the accused. The book, though has a semi-omniscient viewpoint and though the lawyer, Meecham, leads the investigation, we spend a lot of time in many of the other characters' heads. The daughter, married to a sensible doctor husband, is not sensible herself and was found passed out drunk, covered in blood in the cabin of a married man who was known in town to be a playboy. The married man is in the cabin also. Somebody stuck him in the neck several times with a kitchen knife.Things get very complicated and very interesting, as each knew character, as sad and broken as they often are, are worth reading about. What I found really interesting about this book is how much it reminded me of Ross Macdonald. This is early in her crime career, but after she had written a few gothic thrillers and I don't know if she was finding her voice or if her husband was the one finding his voice. She edited (and I believe typed up) his books so there was definitely an interplay between them. I wonder how that worked out. They must have had a solid foundation of a marriage to not get into terrible competition over their writing.

This was a really enjoyable read, but not an exemplary Millar book. It didn't stand out for me like some of her others (Beast in View, in particular). The one really weird thing in this book is when the protagonist and a woman fall in love. It's so sudden and they don't even kiss or anything. They've only met a few times and then suddenly they both admit that they are in love with each other and get all goofy and swoony. I guess that's how it worked in the weird '50s.

Sunday, June 24, 2012

50. The Farthest Shore by Ursula K. Le Guin

Ding ding ding ding! 50 books! Before July! I really don't know what got into me, but that shit is impressive. I think I may change my goal to 100 books [asteroid promptly crashes through my roof]. There are many factors at work here and some advantages that gave me a big boost. But again, I think the biggest thing is just sticking with reading. The more you read, the more you can read. I really have not sacrificed much other stuff in my entertainment life this year. Still socializing as much as I have since I moved to Montreal, still working hard, still maintaining a decent marriage. I have cut out gaming (tabletop roleplaying, not videogaming which I don't really do anyways) and especially all the online BS of that world where I was wasting a lot of time. Also, my wife is like 8 total seasons ahead of me in the various TV shows we watch. And finally, I got this 3-month secondment in California, which has a good hour of readable commute time a day and way fewer distractions of home life. Also, I suspect that come mid-October I will not have much time to read, so I wanted to make sure I met my goal ahead of time. But enough crowing. If I could write like I can read, I might actually have something to be proud of.

On to the third book in the Earthsea trilogy. I enjoyed it, but I have to say it was kind of a disappointment. It's definitely my least favourite of the three and I hope that the other, later Earthsea writings can satisfy me more now. At first I thought it was just the unrelenting gloominess of this book, but looking back on it, I see that it also has some structural flaws that made it feel less rich than the first two.

The Farthest Shore takes place a decade or two after the Tombs of Atuan. At this point, Ged has become the Archmage of Roke. He is the most powerful wizard in the Earthsea and has a rich history of exploits (beyond the ones in the actual two books). Now, there is a darkness emanating from the outer reaches of the land. Wizards are reporting that they are losing their magic. A young prince from an important kingdom comes as a messenger and Ged takes this as an omen. He calls a council and decides to sail with the prince to find the source of the problem.

The first and second books both end with these dark, gloomy and trudging finales where Ged is challenged in a slow, draining way. In the first one, he and a wizard buddy sail way out to the edge of the world to find Ged's shadow. In the second one, Ged is trapped in the labyrinth, clinging to life while using all his magic to hold back the shadows there. These were dark and trying, but they were only at the end of the book. Almost the entirety of the Farthest Shore is this kind of quest. For me, it dragged. There was no joy in this book. The spectre of the end of magic is always a scary one for the fantasy reader. It almost felt like the magic was drained out of this book from the beginning. And though the ending, the darkness is vanquished and the magic restored, the reader doesn't get to experience any of the resurrection that should have followed. We don't get to go back into the rich, magical world of Earthsea that drew us in in the first place.

Worse than that, though, was a real lack of characterization with the prince. In the first two books, Ged and the princess are richly portrayed. The reader grows up with the character. Here, the prince comes ready made and you don't get much from him besides being a witness to Ged's struggle. And this guy turns out to be the one king who will return the single throne to Earthsea. Similarly, the antagonist is a minor character who is only initially referred to in a passing history of Ged in an incident that takes place after the first two books. It just doesn't have a lot of weight. At least for me it didn't.

The worlds they visit are evocative and cool and the underworld quest they go on was compelling such that again I was hard-pressed to not keep reading. But it just didn't give me a lot of pleasure. I felt denied! I know there is at least one other book and several short stories that take place in Earthsea, so I'll reserve my hope for more of the magic of Earthsea in those books.

On to the third book in the Earthsea trilogy. I enjoyed it, but I have to say it was kind of a disappointment. It's definitely my least favourite of the three and I hope that the other, later Earthsea writings can satisfy me more now. At first I thought it was just the unrelenting gloominess of this book, but looking back on it, I see that it also has some structural flaws that made it feel less rich than the first two.

The Farthest Shore takes place a decade or two after the Tombs of Atuan. At this point, Ged has become the Archmage of Roke. He is the most powerful wizard in the Earthsea and has a rich history of exploits (beyond the ones in the actual two books). Now, there is a darkness emanating from the outer reaches of the land. Wizards are reporting that they are losing their magic. A young prince from an important kingdom comes as a messenger and Ged takes this as an omen. He calls a council and decides to sail with the prince to find the source of the problem.