I honestly had thought that I was unlikely to ever read 50 books a year again. I almost abandoned the blog completely as most of my other friends and compadres did in the 50 books challenge. I have always been one to record things, though, and kept it going just to at least have a list of which books I read when. Thank goodness, because a new, unexpected energy seized me this summer and I found the time, discipline, energy and interest to get back into reading again. It's been really great and I hope to keep it going.

I started the blog and challenge in 2005, so 2017 is the 13th year. I achieved 50 books 7 out of the 13 years, but also went way over in several years. I am currently averaging 44.62 books a year. I have a total deficit of 70 books to catch up to make an average of 50 books a year (assuming I also read the 50 each year which cleary has not been a given). My far and away worst year was 2016, where I read only 18 books. Interestingly, this resurgence year, I read 58 books which is the exact same amount I read in 2005, the first year! A real rebirth!

And speaking of birth, I am pretty clear on the various factors that inhibit or support my reading habits. The biggest one is the birth of my daughter in late 2012. I really let go in 2013, after my parental leave (where I was reading a ton, thus the strong 2012 itself). I am not exactly sure how her existence slowed down my reading, I think just a general attack on free time and sleeping. The second factor is job responsibility. I went from lowly but relaxed and available office manager to extremely busy and sometimes quite stressed head of IT and Administration for my org in 2012. I was enthusiastic about this as well and spent more time developing my skills and reading non-fiction. The third factor, and the real killer, is social media. I spent so many hours hunched over my phone or laptop scrolling through twitter and Google+ where I could have been reading fulfilling genre fiction. There were some positive elements in that world. The amazing resurgence of my basketball team, The Golden State Warriors, going from decades of mediocrity to the hated crushers of all your loser teams was an incredible journey and I experienced much of the community around that online. Also, the tabletop RPG world over at Google+ is an incredibly creative and cool bunch and we went through a lot of drama there that presaged all the internet shit that broke out in the rest of the world. Still, there was a lot of time wasted there. I see now, though, that it's not any of these three factors on their own, but rather that deadly cocktail of childcare, work stress and social media. The first two fry your brain to such a point that all you can do once you get the kid to bed is sit there and zone out.

I have a better handle on my job now (specifically disassociating myself from the politics) and a new position in the new year that should be a lot more focused. My daughter is 5 and that brings a whole slew of other issues but also she is more independent and I am starting to find more time to read and even exercise (!). Again, the biggest lesson for me of 50 books is that you never can predict your performance, but things are looking up for next year. My fundamental goal is to read 50 books in 2018. My secondary goal is to try and get past that to whittle away at my deficit. We shall see!

As far as what I actually read in 2017, it was a real hodge-podge, defined only by my burning need to churn through the dust-covered row of books in my on-deck shelf. I did do this, to great satisfaction, which led in turn to me keeping that whole area much better organized because I have more space there now (reading consistently as my friend Dan points out tends to encourage other good habits in life). I did get through some classics that had long been on my list including all the Thongor books but 1 (great fun once I got past the nerdiness), the T.H. White King Arthur stories, a final showdown between Lehane and Pelecanos (Pelecanos wins), a massive sci-fi classic (Cyteen, which was really good) and finally lots of enjoyable and easy to get through mysteries and thrillers.

Unfortunately, my gender balance swung strongly back towards the male in 2016. There were several highlights (as they usually are with female authors in mystery and fantasy), including C.J. Cherryh (still looking for the first Chanur book of hers), another excellent Margaret Millar (and more to come), finally finding and appreciating but not really loving Eleanor Arneson. I am very excited for 2018, because I finally found some Elizabeth Sanxay Holding books and will continue to work on my overall gender balance.

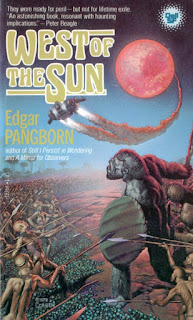

Looking back at the books I read this year, there are some truly exciting finds. Crawlspace by Herbert Lieberman really stayed with me. A Dangerous Energy by John Whitbourn was incredible, one of the best portrayals of magic use and a convincing and engaging story of someone turning evil. He has several more books out there and is now on my list. He also seems to have read my review and since I can't find his books used, I will look for them new. That's a strong endorsement by cheapass me! The Cut by George Pelecanos was just fun. Finally, The Furies by Keith Roberts, which looked really cheesy by the cover (giant wasps destroy the world!) turned out to be an intense and well-thought out PA novel, definitely should be included in the must-reading for fans of that genre.

So all in all a good year, thanks to whatever magic got me back on track. I wish all of you a wonderful and book-filled 2018.

The Jellyfish Season By Mary Downing Hahn

6 days ago