Tuesday, August 30, 2022

45. The Warrior's Apprentice by Lois McMaster Bujold (#3 in the Vorkosigan saga)

Saturday, August 27, 2022

44. Public Enemy Number One: The Alvin Karpis story by with Bill Trent

What struck me about this book was how regional the United States was in the 1930's. It seemed you really could drive for a few days a couple states over after robbing a bank and the cops and FBI did not have a way of tracking you or communicating quickly enough so that you could then rob a bank in the next state. Eventually, it all did catch up with him. His capture spelled the end of the wild Depression-era criminals. This book covers his childhood briefly but mostly deals with the period of his life as a criminal. We really don't learn at all what his 35 years in prison (the longest serving inmate in Alcatraz) were like and the narrative sort of jumps around. It makes it less rich than Sutton's biography, though perhaps even more wild. Similar to Sutton, Karpis was methodical and liked to plan, but he really took some crazy risks and had some bonkers shootouts compared to Sutton.

What stood out for me in the book is his critique of the FBI and particularly J. Edgar Hoover. We all know he was a scumbag today, but when the book was published in 1970, it was probably an eye-opener for people to learn that he totally lied about arresting Karpis (Hoover claimed he arrested him in his car, stopping Karpis from reaching for a rifle in the back seat; Karpis said Hoover only came out after many other G-men had him surrounded and it is a fact that he was in a two-seater with no backseat). Hoover also spread the story about Ma Barker (who was the mother of Freddie Barker, Karpis' partner in the Karpis-Barker Gang) being this evil old lady mastermind. Karpis (and others since) shredded that lie used to justify gunning down an old lady, showing that while she was generally aware her sons were criminals, she was mostly kept in the dark and basically a simple hillbilly woman.

|

| Come on. Cover painting by Andy Donato |

43. Kill All the Judges by William Deverell

It started out a bit too meta for me, with Vancouver lawyer Brian Pomeroy losing it, descending into a drug-fuelled breakdown while writing a novel and taking on the case of a working class poet accused of throwing a judge off his own balcony during a literary party. The drug use and the breakdown was darkly funny and very well-written, but also interspersed with the novel which mixed reality and fiction and I was worried I was going to be confused. I started to get the jist, but then that storyline got abandoned as Pomeroy gets put in an institution and we switch the narrative of (whom I now know to be) Deverell's series character, retired lawyer Arthur Beauchamp. This was immediately fun as he lives on a made-up Gulf Island (called Garibaldi, but could be Pender, Gabriola, etc.). The cast of island characters, various fuck-ups and weirdos was spot on and quite funny. There are a lot of plotlines on the island and Beauchamp's personal life: his wife is running for the Green party, his brooding adolescent grandson has been dumped by his absentee son-in-law, a neighbour sculptor is busted for weed, his truck keeps not being returned by the flakey mechanic. All this is going on while Beauchamp tries to avoid taking on the poet's case (who also lives on the island).

This is one of those very entertaining, page-turning modern detective novels with quite funny dialogue, lots of interesting characters and a nice, dark look at the scummy world of politics and law. Deverell clearly knows his stuff, from the law to island life to excessive drug use. I'll be picking his books up in the future for sure.

Tuesday, August 23, 2022

42. Deathworld 2 by Harry Harrison

In the second book, he is immediately kidnapped from Pyrran by Mikah, a self-righteous activist from the planet where Jason won the money that started his trip to Deathworld. Mikah is a caricature of the puritan. He represents a minority group that wants to stop the gambling on his homeworld by putting Jason on trial and exposing the fraud of the gambling syndicates who are using him for advertising (because he won so much money). Jason breaks free and sabotages the ship and they crash on a super-primitive slave world. They get caught by a slaver whose sole existence is walking a group of slaves back and forth through the desert, digging up these roots for food. The rest of the narrative is Jason making his way up the food chain, first by might and then later by his knowledge of technology. He ends up as the main advisor to the tribe that controls a very primitive form of electricity. His goal is to find a space port and failing that, signalling into space in the hopes of getting rescued. There is a lot of fun as he impresses the tribes with his knowledge, fights a lot and keeps not killing Mikah who keeps self-righteously ratting him out.

Underneath the fun are themes of technology and transparency of ideas, puritanism vs. relativism and morality. Sometimes it is a bit heavy handed, which was the norm for sci fi of these times. The primitive society's biggest flaw is that they hide their technology from each other and the most annoying character is rigid Mikah. It's all writ fairly obviously but its okay because there is so much fun along the way.

Sunday, August 21, 2022

41. From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg

I also didn't quite understand the main theme of Claudia running away and not wanting to return until she had achieved something. I mean I got the part that she ran away to be special, but the idea of her having a secret and that satisfying her was too subtle for my simple brain. I will be taking my daughter to the Museum of Natural History at some point, so we'll see if she remembers anything from the book.

40. Theirs Was the Kingdom by R.F. Delderfield

The family takes up the bulk of the book and to be accurate, because of that, the main character is really his wife, Henrietta Swann. I think that Delderfield made an effort to amplify feminine narratives, even to the point at times of anachronism. A big chunk of the first book, and of the theme of their marriage, is that Henrietta ran his business for a year when he was out after a bad train crash. Here, she manages the family and the various conflicts and crises that arise, mainly around the children finding marriage partners. The first and biggest one is the eldest daughter hastily marrying into class (though rich, because Adam is in "trade" he still is outside the society of the landed gentry). This episode was almost funny and telling in Delderfield's clear disdain for the inbred and deteriorating aristocracy of 19th century England. Her weak-lipped bridegroom brings her to his dusty and ill-cared estate, where he focuses only on his games (billiards and horse-racing; the only source of active income the family has left), drinking and his super close buddy Ponsonby. She soon discovers the reality that her husband will never consummate their marriage and worse that his creepy dad wants to do that in his place, to produce children and hush up any scandal. There was some homophobia in the portrayal of their gay relationship, that I think went beyond the mores of the time. They are portrayed as quite nasty and prancy, though how much of that is Delderfield critiquing the British gentry isn't entirely clear.

We follow all the children in their various adventures and growth. These are often interwoven with real historical events and trends, such as Victoria's jubilee, social reforms around prostitution, even bicycles. I found this book very engaging and easy to read, but at times it was all a bit too easy for the children. Other than Stella's adventure, which had the real risk of a ruined reputation and legal conflict with a neighbouring family, none of the stakes seeemed all that high, even when the stepdaughter Deborah goes deep into Belgium to expose sex trafficking. Everything works out in the end for the Swann's. Ultimately, I appreciate that and I think that's what readers of this kind of book look for. Regular readers will know my own dislike of the dogma of necessity of conflict in fiction. It was just at times it all felt so easy for the Swann's, especially when they have absolutely financial troubles while also getting to be just progressive enough to never be bothered by any social ills, it does all seem a bit fantastic. There is a third book to come, so this direction could reverse significantly as the British empire heads into the Twentieth Century and the beginning of its end.

It really is an escapist fantasy. By the end of the book, Adam Swann has retired from his business and let his son take over. He then gets to spend the last few pages of the book completely re-landscaping his big property and decorating the interior with all the cool things he has accumulated after years of shipping goods all over Britain. It did make me regret that I haven't spent my years amassing wealth and a huge estate so that I could spend my dotage planting cool gardens and building lakes surrounded by exotic trees to go and feel peaceful in.

Tuesday, August 09, 2022

39. Deathworld by Harry Harrison

I have to applaud again the now mostly outdated practice of the shorter fantasy or sci-fi book. I do enjoy the depth of detail and absorption of a thousand-page per book trilogy but authors like Harry Harrison show that you can deliver epic scope and cool characters in 150 pages. The hero is Jason dinAlt, an itinerant gambler/cheater whom we learn has a psionic ability to read and manipulate objects of chance. Kerk, the ambassador from the planet Pyrrus hires him to turn a 17 million credit front into 3 billion dollars. Jason succeeds and he and Kirk barely escape the casino security. Jason learns that Kirk has a deal to use the money to buy a ton of armaments to take back to his planet, which is so deadly that the small group of colonists who live there spend all their lives just fighting it to survive. Jason, intrigued, convinces Kerk to let him come and visit. In order to survive, he is forced to join the training program with the six year-olds.

At first, it seems like most of the book will just be about exploring this super deadly planet, but we quickly get into a greater plot, where Jason suspects there is more going on than just a hyper-dangerous environment. His investigation leads to some pretty big ideas about man vs. the environment and conflicting types of society. It goes quickly and therefore seems a bit too easy and simplistic, but we appreciate this is a function of the speed of the book. It also ends nicely with an option for greater adventure (which I will explore in Deathworld 2). Good stuff. I am glad to be rediscovering Harry Harrison.

Sunday, August 07, 2022

38. The Stone Sky (book 3 of the Broken Earth trilogy) by N.K. Jemisin

My complaint is that there is at times what feels to me like a forced conflict in Essun's (the mother) relationship/feelings about herself and her daughter. I find at times in post-colonial sci-fi there tends to be a self-criticism that feels forced and rings false. She blames herself for things she did or did not do that are completely outside of her power. There is a lot of "I am a failed mother because I couldn't protect my daughter" when there was absolutely no way to protect her and the earth being ripped in half separated them. It was lightly applied enough that it only got in the way of the story a few times. However, at the end it really threw me off. The mother and daughter finally meet and if they had just shared a few sentences with each other, a lot of fake conflict would have been avoided. Instead, the daughter goes storming off. I'm sorry, no matter how tough the mom had been with her, after two years and all they had gone through, there would have been some greeting and interaction before they started blasting each other with their magic power. It just felt forced.

Maybe I am too much of a male doofus to get the subtleties. As I say, this was a minor flaw in what was otherwise a really cool epic journey that pretty much did everything you want an epic fantasy book to do.

Monday, August 01, 2022

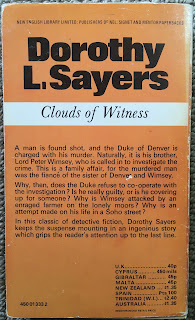

37. Clouds of Witness by Dorothy L. Sayers

A big part of the charm of these mysteries is reading the lifestyles and interaction of the aristocracy. Clouds of Witness is rich with these elements as the murder takes place in (or rather just outside) a house the family is leasing for shooting and Wimsey's elder brother, the Duke of Denver, is the accused. I don't know how much of his history and family play a role in the rest of the books. Here, though it is his older brother, Wimsey displays British "business as usual" and adds no extra emotion to his detecting (we also learn that he doesn't really like his brother all that much, which is later affirmed in a biographical note added to the end written by their uncle).

The mystery here wasn't too tricky and I appreciated that it seemed more of a vehicle to get Wimsey, his man Bunter and his confederate in the police Parker to have adventures and interact. Really, the crime is complicated by a series of coincidences. Basically, his sister's fiance is found dead, shot in the heart. The brother discovers the body and is bending over just as the sister comes downstairs and she thinks her brother shot him. Both of them are also hiding something. And it has come out that the fiance was a cheat at cards and the elder brother had found out.

It's sort of hard for me to distinguish between the styles of Ngaio Marsh and Sayers at this point, as both have aristocratic detectives with a backstory and I've only read one of the latter. Sayers has a slight lead for now in that the one book I did read was not so fiendishly complex and obsessed with the revelation of the crime.