Friday, September 23, 2022

49. Deathworld 3 by Harry Harrison

Tuesday, September 20, 2022

48. The Kappillan of Malta by Nicholas Monsarrat

The book is structured around the historical sermons that the priest delivers to lift morale. These are interludes that allow Monsarrat to relate several important chapters in Malta's history where they dealt with war and invasion and survived. Each was a great little mini-fictionalized history, informative and entertaining. I learned a lot about Malta, of which I was almost totally ignorant. It's also quite moving, with many great characters, especially Nero the super positive dwarf. His introduction, as the only voice of spirit during a boat ride after the first bombing, is particularly compelling. "Nero wheeled round, and began to run and jump and skip up the street, as if he could not wait to confront his next problem." There are no direct antagonists, but the two most hateful characters: manipulative and small-minded monsignor Scholti and traitorous brother-in-law Lewis Debrincat are extremely effective. There is also a romance between his niece and a cliched but still well-drawn rakish British pilot.

It has a relaxed narrative, confident that the situation itself is compelling, not needing forced conflicts. I found myself caught up in Father's Salvatore's various plights and problems, even his spiritual agonizing. Great read.

Tuesday, September 06, 2022

47. The Heroes by Joe Abercrombie

What can I say here of any depth, beyond that it delivered exactly what I had anticipated. Another easy to read, enjoyable, funny and brutal fantasy novel. The Heroes is fun because it is very focused, unlike the epic First Law trilogy that precedes it. It all takes place in three days in a single location. The story is entirely about a battle between the "barbarians" of the North and the civilized Union of the South. Not only do we get a beautifully illustrated map of this pastoral valley, but each of the three sections of the book updates the map with the various military positions at the end of each day. This was all super helpful for me to picture the action and be clear on what was going on, though I suspect that Abercrombie's writing is clear enough that one could still figure it out without the maps.

Many of the characters from the First Law trilogy show up here and some of the lesser ones get a full expansion. We also have some new ones. As usual, we get all the wide range of grim, cynical and funny characters that make the other books so enjoyable. If you are more into the fantasy and politics and less the fighting and Named Men, you may not love this one. However, if you are into crunching medieval combat and rich, funny brutal warriors, this is the book for you. He even has an annoying warrior keener, in Whirrun of Blight, who loves to fight and is always super enthusiastic, a hilarious counterpoint to the mostly grim and weary members of his dozen.

Just a lot of fun and it reminded me how much I enjoyed The First Law. There is another trilogy taking place the next generation down that I will be keeping an eye out for, but will have to save it for later is it will always be readily available and I have an overflowing on-deck shelf to deal with now.

Thursday, September 01, 2022

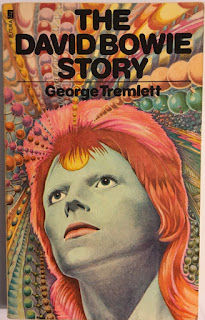

46. The David Bowie Story by George Tremlett

Seriously, the bulk of the first half of this book is a fawning apologia to Kenneth Pitt who was indeed Bowie's first agent and whom Bowie dismissed after a few years. The tone has a slightly moralizing, superior air, chastising Bowie for not doing things the way Pitt and a traditional pop star should and elaborating on all the ways Kenneth Pitt (and his lovely house in the country) is a decent and cultured man, not at all like most music agents. I almost suspect the author and Pitt were lovers. We do get some actual facts about Bowie's upbringing, though even there it veers into how not only did Bowie not invite his own mother to his wedding, he didn't invite Kenneth!

The second half is a bit more informative, with a fairly detailed narrative of Bowie's tour in the United States, his growing relationships with other celebrities at the time and his own struggle with early fame. When you peel away the inconsistent structure (he jumps around a lot in time and often repeats the same message in slightly different ways), though, there is a nice history here that gives some insight into Bowie's mercurial creativity and the scene he came out of. I always respected Bowie's work, but it never grabbed me and I think a big part of that is because he is really an experimental artist who was constantly trying everything within the framework of popular music and culture. I am guessing that some have accused him of simply being a chameleon, but reading this book did make me feel that he was genuine in his artistic exploration (unlike say the more cynical Madonna) and definitely a truly talented and charismatic performer.