Monday, February 27, 2023

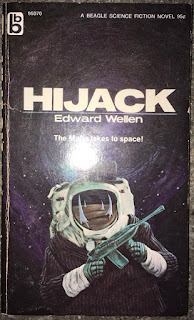

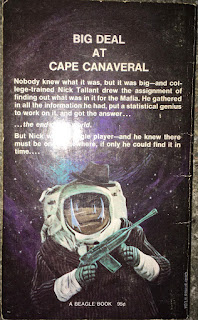

19. Hijack by Edward Wellen

18. The Question of Separatism by Jane Jacobs

The initial chapter is basically a call for rationality and to remove emotion from the discussion. She calls out both sides, though is sympathetic and understanding, for making completely unrealistic arguments and statements. She then makes a really interesting historical argument, demonstrating that Toronto had actually started outgrowing Montreal as the major economic hub of Canada decades before the Quiet Revolution. This was a real revelation to me as the conventional wisdom is that the french took control, started imposing language laws and all the big companies fled, thus flipping Montreal and Toronto's status. Jacobs demonstrates how mining growth in Ontario and its investment in Toronto pushed the TSX past the Montreal exchange and started to move money from the big banks in Montreal to those in Toronto.

She then goes into the history of Norway and its peaceful separation from Sweden in the 19th century. This chapter was really interesting as well. I didn't know any of it, particularly that Norway had neither its own true language nor a self-identified Norwegian culture until this period. The next chapter she argues convincingly that big or small are not definers of an economy's strength and quietly and gently rips into Canada for using it's population size as an argument for why it's economy is so fragile. She calls it a "colonial economy", dependent on resource extraction with minimal effort in developing domestic manufacturing and small and medium-sized enterprises. This situation has improved somewhat since 1980 when this book was written, but not much. This is why Canada is still so keen on fossil fuels and a relatively large emitter of fossil fuels. Also why Canada, despite some positive examples like the videogame industry (in Montreal), is still lacking in innovation. It's really kind of depressing how we lag behind small countries like Norway when we have all the same advantages and more. The one thing we have that they don't is a culture of small-minded penny-pinching fear of change and a powerful cabal that works to ensure they have all the money.

Anyhow, it was quite a surprise to read that Jacobs was a proponent of separation. But when you get to the end, she makes a strong argument for diversity and then it makes sense that she would support a separate Quebec. She argues that despite the inherent limitations of our colonial economy, a separate Quebec would create an economic diversity (layering on the existing diversity of culture and language) that would benefit both countries. This aligns with her arguments about mixed spaces in cities. I wonder if this book was ever translated into french and how it was received in Quebec. According to my sister, it was not that well received in english and that in general Jacobs post-Cities works, as is typical, were poo-pooed by the Canadian literary establishment.

Sunday, February 26, 2023

17. There's Always a Price Tag by James Hadley Chase

The story here is told from the perspective of Glyn Nash, a smart, good-looking guy down on his luck in a dead-end advertising job in L.A. He is sitting in a bar when he sees a guy stumble out and blindly walk into traffic. Nash saves him from getting hit by a car and then offers to drive him home. The man turns out to be Erle Dester, a famous once-successful movie producer who is on the verge of drinking himself to ruin. He offers Nash a job as his chauffeur and dogsbody for quite a good sum. Nash is reluctant until he meets smouldering hot Mrs. Dexter. Against his better judgement, he takes the job. He soon learns why the house has no other servants, why most of the rooms are closed off and covered in dust clothes and why Mr. Dester is drinking himself to a stupour. Mrs. Dexter, as soon as she learned that her husband had taken out a massive life insurance policy on himself in her name, became "frigid". And now Nash strongly suspects she is waiting for him to die. Even more against his better judgement, he decides to try and team up with her.

This is a very procedural and more complicated take on Double Indemnity. We have the super smart, relentless insurance investigator, but he only really comes around late in the game when everything is already going to shit. This isn't really a morality play and if there is any kind of deep theme it's that planning an insurance scam that involves murder (even if in this case, it doesn't actually involve murder) is incredibly complex and almost certainly will fail. The enjoyment of this book is following Nash in his planning and then stressing along with him as little things keep going wrong here and there, each not enough to totally derail the plan, so that he keeps going along with it until things of course finally do not work out at all. The fun part is that one of the crucial elements in the plan is to put Dester's body into a deep freezer so they can take it out later and fake the actual time of death. There is a lot that is preposterous about this plan, but it is still quite enjoyably goofy.

The ending petered out a bit as he basically just gets caught (no spoilers because he foreshadows it at the beginning) though there is a minor ironic twist a little before the very ending.

Also, I am not sure if it is me or if Chase was relaxing his American cover a bit by this time (written in 1958) but it felt more english in style to me. First of all, I don't think anybody was called "Glyn" in America (nor "Erle") but mainly there was a "should" instead of a "would" in the first page.

Thursday, February 23, 2023

16. The Inconvenient Indian by Thomas King

The other weird thing was that just after I picked this book up, there was some news item about how Thomas King had been revealed to not be a Cherokee after all. That put me off from reading the book, but when I went to research it, it seemed to all go away quite quietly, though his bio makes it clear that he is "not tribally recognized". This is a very tricky subject, but just look at the guy. I'm not going to opine too long, as if there is a sin here it is if he somehow benefited from his being or claiming Indian to get a job that another Native American might have gotten. There are probably deeper post-modern issues as well, but I suspect the guy's dad really was Cherokee but he was raised basically as a normal white kid while knowing about his dad's background (he was raised by his mother). Anyhow, the point is that from what I can tell his work has done a lot of good in raising awareness at least.

I was also at first a bit annoyed by the breezy tone of the book, especially all the first person and references to his wife. But once it gets rolling, that breezy tone makes the book (and its important info) very easy to digest and sometimes quite clever and funny. He is an older guy and wrote mainly fiction, so I totally sympathize with his struggles writing this book. I hate to say it, but I would have to use the term "important". It delivers a solid and brutal list of all the various mutating ways the American and Canadian governments have systematically attempted to "Kill the Indian" since the European colonists first arrived. What's clever about the book is that it frames it in the broader argument that it is basically all about getting the land (and the resources therein) and basically trying to eliminate the Indian as an annoying (inconvenient) problem blocking progress. So you see all the various phases of government policy with different names and tactics but all basically boiling down to the same end goal. His tone is light throughout and thank the Gods because even with that, it is some brutal and infuriating reading.

He does end on a somewhat positive note (though with many qualifiers), discussing the Alaska and Nunavut treaties. As I read this, I can hear the pro-oil and logging fucks going on about the economy and jobs. At what point do we take capitalism's cock out of our mouth and find a way to live on this planet without consuming every last molecule so we can have two cars and get likes on instagram? This book is a strong reminder that we can create a world where our priority is well-being and not profit and a huge part of that is truly redressing the wrongs of colonialism giving power back to the indigenous people of the land here.

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

15. Neon Wilderness by Nelson Algren

On the positive side, Algren is a great writer. The locations and situations of the petty criminals and losers of Chicago are rich and well told. There is lots of drinking and fighting (his boxing scenes are really good; detailed and punishing). Prostitution at the lowest levels is standard work for most of the women characters. The men are all stealing or up to some kind of scam. Everything is quite depressing. There are few scenes of redemption or happiness and they are of the humblest sort, such as the boxer who loses the fight he was supposed to throw even though he doesn't want to and learns that his girl bet all of his payout on him. They lost it all, but are happy because they still love each other. Most of the stories are just sad.

I think what bugged me was that deep down underneath all these stories, though they are portraying a reality that didn't tend to get written about in literary journals, are basically moralistic. Nobody is going to get out of their situation and it kind of feels like they aren't supposed to. They definitely aren't supposed to get any pleasure out of their lot. I wasn't around in Chicago's poorest neighbourhoods in the thirties and forties and glad I wasn't but I do feel despite the poverty, there were probably moments of happiness and joy for the people lived there. You wouldn't get that from Neon Wilderness.

Friday, February 17, 2023

14. Chanur's Homecoming by C.J. Cherryh

I really could not remember where we had left off from The Kif Strikes Back, but there is an excellent summary chapter at the beginning that not only lays out the previous storyline, but also gives good summaries of the various characters and species. Still, it took me a good 80 pages of the first 400 to really get caught up with who is who and what was going on. This series is complicated! You have 4 oxygen-breathing species who though can be thought of as sort of animal-equivalent (the feline Hani, the simian mahendo-sat, the insect-like Kif and the avian-ish Shtsho) are each complex enough in their depiction and language that that simplification isn't too helpful. Also, humans get added to the mix, though we never get their point-of-view nor a clear understanding of what their space empire is actually like beyond that there are 3 warring governments and they may have some relatively high tech for space travel. There are also 3 mysterious methane-breathing species, hard to know because their language is almost unintelligible for the protagonist Hani and one, the knnn, that nobody seems to know anything about other than they are super powerful and just show up and take stuff and leave other stuff behind (which is better than just destroying everything by taking it apart which they did before).

I'm sort of impressed with myself that I got all the above without referencing it on the internet. It's also a testament to Cherryh's writing skills that she can get this to the reader while delivering the narrative. She does it with very little exposition, though does rely heavily on Captain Pyanfar Chanur's inner monologue. All these species are fighting/negotiating/scheming/allying with each other while also having their own internal political struggles. Language and culture are also major factors so you have not only representatives of each species trying to interact with each other for their various ends, but they also can't understand each other or misinterpret behaviours. We as readers are not given any omniscience, so we also are trying to parse the limited pidgin of the mahendo'sat or the hissing menace of the kfff and even the maybe 2 dozen human words the Hani interpreter software can badly translate. It makes for a tough read, but it feels very real. If you want a rich setting with multi-species space politics as it might play out in a "realistic" way given the limitations of cultures and languages, this book delivers. Even though it was written in the late 80s, it does not feel anachronistic or coming out of that period. Likewise with the actual space travel and hyperspace jumps (though the mechanicalness of it all might be a bit 80s).

The basic plot here is that it turns out the mahendo'sat have been playing two warring factions of the kfff against each other while secretly allying themselves with the humans (who turn out to be much more powerful than previously though). Their big play involves driving the kff towards the Hani homeworlds to hem them in, but also putting those homeworlds at risk. Pyanfar has to figure this out by playing a delicate game of diplomacy and then by a brutal race of hyperspace get back to protect her homeworld while also dealing with another Hani backstabber and her people's own worldbound and conservative politics whose rigidity may doom them all.

I struggled with the political shiftings as I couldn't always figure out what Pyanfar herself was figuring out. Likewise, the science of the hyperspace jumps with their "V"s and their nadirs confused me. Nevertheless, it was a real page-turner and quite stressful. It was actually a bit too stressful and anxiety-ridden at times for me with so much internal monologue, constant fretting and exhaustion. You are wrung out but satisfied by the end. I'm still skipping several other layers of nuance, like Pyanfar's husband the first male in space being on the ship and her having a kff on the ship with her and its dinner strange little rodent things escaping into the ship and causing damage. There is a lot! The coda, where a young male spacer gets lost and accidentally encounters his hero (because thanks to her male Hani are allowed in space now) was just great.

This stuff is for real sci-fi nerds, and if you are one, I think it is fair to call it a classic.

Wednesday, February 15, 2023

13. Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini

|

| Mine didn't have the slipcover |

It's funny because this is the second book this month where a decent man gets kidnapped and thrown on a boat to the new world. In Captain Blood, the politics are forefront. In treating a wounded nobleman who fought in the failed rebellion against Catholic King James, Blood is arrested for treason. Instead of being hanged, the set of prisoners with which he is charged are sent to the new world colonies as slaves. The brutality is notable. This book was considered a populist entertainment of the time. The treatment of the slaves, in this context, is a harsh reminder of how the "civilized" world used to be, even to their own race.

Fortunately, for Peter Blood, his skill as a doctor (and his far superior bedside manner) slowly gets him excused from the killing toil of the rest of the slaves. Here we meet the nemesis of the book, the cruel bastard plantation owner Colonel Bishop, as well as the love interest, his niece Arabella. Blood, with the interested help of the other two doctors (who are envious of his success) escapes with a bunch of slaves and begins a life of piracy. The narrative is a serial of piratic battles and adventures that would make a great TV series. Eventually, it all circles back to Colonel Bishop (with a middle interlude defeating a Spanish admiral) with a most satisfying conclusion. All these adventures are fun, though at times some of the story felt a bit eluded. I will keep Sabatini on my hunting list.

Monday, February 06, 2023

12. The Asphalt Jungle by W.S. Burnett

Anyhow, on to the book. I actually was going to read this phat phantasy novel that I had bought for my brother-in-law for xmas and which he had rejected because he couldn't get into the prose. I too found it a terrible slog and had to abandon it about 50 pages in. I have not done that in ages, if ever! Very discouraging. So I was very happy to jump into The Asphalt Jungle, which begins with a pretty clear situation and solid prose. A large midwestern city (which I assumed to be Chicago but then one of the characters runs away to Chicago later in the book) is rife with corruption and has just brought on a new, no-nonsense commissioner who is going to clean it up. The framing device is an old, cynical journalist who decides to give the commissioner a chance. Soon, though, we zoom in to the real story. An unassuming, German-American, master criminal has just been released from jail with a promising big heist already planned. He just needs a string and a sponsor.

Burnett does a fantastic job of bringing us into the milieu and the people of the criminal underworld (and not so "under" with most of the cops on the take and semi-legitimate bookies operating almost in the open). The hub is a little greasy spoon counter and magazine stall run by Gus, a tough, connected well-respected hunchback (and driver when needed). He leads Riemenschneider to a great cast of characters, Louis the tool guy trying to go legit, Cobby the money man who is also connected to a big-time defense lawyer Emmerich who has the real money and finally Dix Hendley, the hard southern hick tough who is wavering about his career and his feelings for Doll, the aging nightclub girl.

The entire middle of the book is just clean, efficient criminal machinations as they plan the heist and execute it. It's great. Of course, it goes pear-shaped for a variety of reasons and we watch as each character meets their fate. The bigger idea is that each guy had a flaw that brought them down, but what actually happens is a bit more complex and therefore more interesting. Ultimately, the main thread is competent Dix who really just wants to get back to his family's farm. This gets a bit heavy and maudlin at the end, but still moved me.

Saturday, February 04, 2023

11. Sackett's Land by Louis L'Amour

This one is not a western, so perhaps not indicative of L'Amour's style. It's a bit preposterous, somewhat light but mainly a lot of fun. I prefer my adventure books to have a bit more subtlety and be slightly harder on the hero than what we have here. Sackett's land is basically an empowerment fantasy. The hero, Barnabas Sackett is a poor man of the fens (these cool marshes) who is seemingly at the very bottom of the pecking order of life (and England). Yet, he is incredibly strong (can wrestle two men), skilled in hunting, fishing, fighting with sword, gun and bow and sailing. Furthermore, though of the lowest class, his father was a soldier who saved the life of a nobleman and though Barnabas never met the nobleman, he is looking out for him and wants him to be his heir. So he even cheats class restrictions.

Despite his layers of privilege, Barnabas starts out in a bad way, having accidentally insulted a dick Earl who is now out for his death. Despite my critiques above, there is a ton of cool adventuring in this book. I especially enjoyed the description of the cultural and geography of the labyrinthine fens in the beginning. He meets a diverse case (except all male but one the love interest) of cool other adventurers, all down in their luck but ready to latch on to a strong leader. We get a moor, a continental soldier, an Italian and my favourite, Jeremy Ring, a sailor looking for work. All are good men, chafing under the oppression of English class hierarchy and criminal scoundrels.

The bulk of the story takes place in the new world, involving a battle between the good ship and the bad ship (which the evil earl has also paid to get rid of Sackett). Everything moves quickly, a bit too easily despite many battles and setbacks (like these guys are good at making bows and arrows!) and yet somehow all very satisfying and moving. I'm definitely putting the next book in the Sackett series (To the Blue Mountains) on my list.

|

| cool insert offer for books by mail |

Friday, February 03, 2023

10. The Wind's Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Legion

Overall, these stories reminded me of what a great writer Le Guin is. Among other things, she is a master of setting and evocative details that pull you in. Unfortunately for me, she is also to smart and too driven by real issues to leave it at that. I wish she would write a simple adventure book with wizards fighting each other, but her stuff always goes deeper and way darker which is why I take a long time between books. In this collection we get both the fun and the deep, with a few misses along the way to remind us that she is indeed human.

Each story has a nice little intro by Le Guin, which helps to put them in context and get a sense of playful personality (as a writer at least) in 1975.

Semley's Necklace - interesting study of alien life forms, time passing too long

April in Paris - time travel via an old apt in Paris

The Masters - intolerance of science in a post "Firefall" world where everything is done by rote and a builder starts to figure out how numbers and algebra work and gets his hands smashed in punishment

Darkness Box - neat story about a magical world where time is stopped - one brother with a hypogriff goes and fights his invading brother on the beach over and over -- and a little boy gives a box of darkness that starts time.

The Word of Unbinding - really cool in the Earthsea archipelago world, a wizard is attacked from behind and imprisoned from some rumoured invading and destroying wizard and he uses all his magic to get out and defeat him.

The Rule of Names - another really cool won in the Earthsea archipelago world about an island with a kind of weird, incompetent wizard (every island should have one) who turns out to be a powerful dragon on the dl. These two stories remind me of how good LeGuin is at fantasy world building and details and how great Earthsea is before it gets so dark.

Winter King - from the same universe as The Left Hand of Darkness, a cool mini-saga about a good young king (a she) who is kidnapped and mindmolded so that she will become a tyrant, her only choice is to abegnate and leave the kingdom to her son. Wish it had been expanded into a novel.

The Good Trip - ambiguous and not very good description of an acid trip that wasn't or maybe it was. Had an unconvincing back story of a wife lost to depression.

Nine Lives - very cool story about a team of ten elite clones on a distant planet working with two normal, flawed humans on a mining project. When nine of the clones are killed in an accident, how does the tenth now respond?

A Trip to the Head - a surreal experiment, I guess that helped her to break through writer's block but it's a mess and not enjoyable. LeGuin says in the intro that the only drug she has done is tobacco and I believe her because whenever she tries to go trippy, it's bad.

Vaster than Empires and More Slow - a really cool story about a group of deep space explorers all with various mental issues (because nobody else would volunteer for a program where they come back hundreds of years later) who land on a planet that is all grasses and plants. One of the members, Osden is an extreme empath who is a total asshole. As his behaviour starts to make the rest of the team fall back into their own various pathologies, he is sent out to explore on his own. He is attacked and the group all start to fear that something is out there, though their instruments show no sentient life. This is a really neat examination of isolation versus connection and how knowing everyone else's feelings could create negatively spiralling resonances.

The Stars Below - an astronomer is burnt out of his home and observatory for heresy and is hidden in an abandoned mine by a sympathetic noble. There he discovers a small group of ex-miners who befriend him and he learns to look downward for the stars. A neat, tight little tale that highlights one of Le Guin's many strengths: her ability to elicit rage in the reader at the forces of social repression. Fuck those priests!

The Field of Vision - A trio of astronauts return from a trip to Mars where the discovery of some rooms appear to have killed on, rendered another deaf and unresponsive and blinded a third (though sort of the opposite; everything is too bright). It seems that they have seen god, the room was a kind of proselytizing space.

Direction of the Road - another really innovative and tight piece told from the perspective of a tree. The conceit is that it believes it is moving towards and away all the things that come to it. Very anti-car. I like.

The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas - a political parable (that she calls a psychomyth) about a near utopian society whose happiness and existence is dependent on an abused child kept in a locked room. Definitely a critique of liberal complacency and moves neatly into the last story...

The Day before the Revolution - kind of an origin story of the world of The Dispossessed, it looks into the final days of Odo who was the leader of the Revolution that led to the anarchic world of Odo. It's more about getting old but neat to see some of the ideas that are more fully fleshed out in the novel.